|

Interview with

Kaneko Kenji

Jump directly to interview

Kaneko Kenji, Chief Curator of MOMA

Museum of Modern Art, Crafts Gallery, Tokyo

PRELUDE: Readers, get ready to spill the beans.

February 3rd marks Setsubun (節分), or the turning of the seasons. Tradition has it that we chuck soybeans inside and outside of buildings and entrances to rooms, while chanting, "Luck in, demons out!" In essence, this ritual is meant to purge the evil spirits lurking within our homes, and allows for new and better karma to seep in and bring us good fortune.

I get a kick out of doing this.

But cleaning the mess afterwards is a different story.

First, I'd like to announce the winners of the 2004 Japan Ceramic Society (JCS) Prize announced just last week. This year, three potters were named -- Tashima Etsuko (1959 - ), who like Kondo Takahiro works in the mixed media of glass and ceramics, Hayashi Kuniyoshi (1949 - ), a Seto potter famous for small white porcelain people, and the 8th Kiyomizu Rokubei (1954 - ), the latest Rokubei to spring from the grand pedigree of Kyoto Kiyomizu-yaki potters.

I must admit that I was somewhat disappointed in the selection, but then again, it seems as if the venerable Japan Ceramic Society is running out of ideas. In other words, there have not been many exhibitions that have garnered the attention and captured the hearts of the media, fans, and critics alike.

You have to give potters like Miwa Kyusetsu XII credit, for he undoubtedly caused a ripple when he debuted his golden Hagi chawan in 2003. Likewise, Nishida Jun also stirred positive commotion in 2004 for his massive porcelain objet. However, not only is he too young to be given such an award (it does seem that years of pottery experience factors into the equation), his latest exhibition (ongoing in a tiny gallery called Meguro in the outskirts of Mie Prefecture) was not accessible to many viewers.

Hayashi did gather much praise from fans and critics for his miniature dolls, first exhibited in 2003 (note: might have been a bit earlier). He was always known as a talented vessel maker, creating delicate porcelain enamel overglazed wares, and the departure from his common path was both brave, good-natured, and, ultimately, wonderful. Porcelain sculptural artists are few: some are Fukami Sueharu, Nagae Shigekazu, Nishida Jun and Kato Tsubusa. But Hayashi has indeed made an unique little world that combines nature with Chinese and Japanese aesthetic influences (in particular Chinese). This originality is what puts Hayashi in an arena of his own.

Tashima was most likely credited for her long-standing contribution to shattering the male-dominated status quo of Japanese ceramics, much like Tsuboi Asuka, who received the Gold Prize of the JCS in 2003. Granted, Tashima is an extremely controversial and acclaimed artist, who first made a name for herself in the 1980s for works that embodied feminist ideals and female empowerment. Works materialized as metaphors for the female body, and culminated in the "blooming" of the female sensibility -- behold, her ceramic/glass mixed media flowers, which are a symbol of female sexuality, individualism, and creativity.

As I write about Hayashi and Tashima, I am more and more convinced that they very well deserve a JCS prize. But in regards to Kiyomizu, I emphatically disagree.

He is a name, but name alone should not be deserving of a prize. His works have done nothing to heighten our awareness of ceramics or of ourselves. He is merely following the conceptual footsteps taken by his father, the 7th Rokubei, in making large installation works that dominate a given space. His works are intellectual, but they do not carry much more than brain power, or in other words, a domineering quality of man over clay.

Interview with Kaneko Kenji

Below, you will find the translated (and truncated) version of my interview with Kaneko Kenji, Chief Curator of the Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo (Crafts Gallery). I was going to bypass writing about him, as I had grown bored of complicated conceptual ideas as of this moment, and for the fact that after completing his interview, realizing that he had far less exciting things to say than Sugiura Yasuyoshi's interview.

But since I've translated Sugiura-san's interview, I figured I should at least allow for the other side of the argument to be given light. Hence, this interview.

The Japanese version of this interview is much more tame than my previous interview, for several reasons.

- Kaneko is not a potter but a pundit, and my interest is in the former and not the latter

- I work with Kaneko-san, and he's a nice guy (even though I often disagree with his views)

- As Kaneko is known for compelling, albeit incomprehensible writing, I wanted to show in this interview that he had a pop side to his persona as well.

- The thing is, the pop element has been largely edited out in the version below, as he begins to rave about Japanese pop stars who many of you will not know. I didn't.

- Not only the pop element, but much of the controversial material has been edited out, as it did not chime well with my editors over at www.yakimono.net, who try valiantly to keep the peace within the yakimono world we live in. Peaceful coexistence is key.

That said, I apologize for the stiff academic language of this interview. There was no escaping it, I assure you. And for those interested more in Kaneko's theories and not his personal evolution, please skip down to the chapter titled Blossoming of Ceramic Art Theory.

From Buddha to Curator

K = Kaneko Kenji W = Wahei Aoyama

W: I'm pretty sure that fans of Japanese pottery have heard your name before, either through your writings or through the fact that you are the Chief Curator of MOMA Tokyo. But for those who've read your writings, I think some might feel as if they are a bit difficult to comprehend.

K: Oh really? (chuckling)

W: But on the other hand, I've had the pleasure of reading some of your lighter musings on pop culture and movies, such as Die Hard, which is one of your favorite films. So I have to say, you give off this wide, wild gap between two polar personas, and I was curious to get to the center of this divide. Hopefully, I can pull out some of your softer, more poppy sides, while also discussing the harder, more intellectual yakimono theories, within the course of this discussion.

K: Understood.

Kaneko Kenji, Chief Curator of MOMA Tokyo

W: So, I'd like to begin by asking this: how did you happen to enter the world of ceramic art? I assume you probably liked art in your youth.

K: True, I did enjoy art, but more in the line of literature and music. Both of these are influences from my father. Since I can remember, music was always around me. My father tried to teach me how to play an instrument, but I never took his lessons seriously. And when I realized that yes, I want to be a musician, I was too old and untalented. But I still wanted to learn something pertaining to art, and I wanted to study Philosophy. And in Philosophy, there's a subsection called Aesthetics. I thought Aesthetics was just right for me. But you know, when I got into college, I found Aesthetics to be pretty hard!

W: True, I've tried biting through it during my years in college.

K: Philosophy is hard as well. But since it's tough, my enthusiasm for the discipline gradually started to fade. But at my university (Tohoku University, a prestigious national university located in Sendai, northern Japan), right next to the aesthetics department was the art history department, and in the art history department, there were a bunch of books on Buddhist statues. And I have to admit, ever since I was in elementary school, sculptures depicting Buddha really were my favorite things.

W: Now that's a peculiar kid.

K: I remember when I was in 6th grade. I was on a school field trip, and we ventured to the Byodoin Temple (outside link) in Kyoto (Wahei note -- Kaneko-san himself was born and raised in Mie Prefecture). There, I saw the most beautiful statue of Buddha. I was standing outside the small pond in front of the famous Hall of the Phoenix, and there, enwrapped in soft light, stood Buddha. I thought it was the most beautiful thing I'd ever seen. Ever since that day, I told all my friends how inspirational that experience was to me, and I became famous in my class for being a Buddha lover.

W: Quite a story.

K: So back to college. I began to hate Aesthetics, and when I happened to wander into the art history department, there were many books on Buddhist sculptures. Wow, even Buddhist sculptures can be a subject for academic study, I thought, and I soon wanted to study the topic. I was still a part of the Philosophy department studying aesthetics, but for my dissertation I wrote about Buddhist art, and in particular, the sculpture of the Asuka Period (6th to 8th century AD). After that, I continued researching Buddhist aesthetics in graduate school.

W: So, then when did you first become acquainted with pottery?

K: Back in college, we had a core curriculum wherein we learned Japanese traditional painting, as well as Western art history, in particular the Renaissance. "Hey, a chawan is something you study as hobby," my teachers used to say. I wanted to study other things like craft art, but Japan's art history world had this perplexing stereotype in which people would treat you like a filthy animal if you studied something other than Buddhist art or the Renaissance. Seriously, you weren't considered human if you studied another subject.

W: Talk about myopia!

K: I also was interested in doing modern art, but that made me an outsider. And the fact that I wanted to study modern craft art, wow, I wasn't even in their peripheral vision.

W: That's the problem, right there. Japan had changed its mentality to something similar to the West, where craft art was ranked below fine art. Before, there was no such hierarchy.

K: Exactly. That hierarchy suffocates discussion. But for me, I was studying "proper" Buddhist art. I was safe. But to be honest, "Buddhism" in itself never interested me either. I could study Sanskrit and get good grades, but it didn't ring any bells. And that's why I knew that in the realm of art, I liked the statues, but not the religious Buddhism behind it.

Of course, I wanted a job straight after college, but there were no openings whatsoever. For people who study art history, it is very difficult to find a nice job at a museum right after graduating, as vacancies hardly open up. Only 20% get jobs right after college. So we art students find part-time jobs to make a living until a vacancy opens up. And after a year, the Suntory Museum offered me a job. And "luckily" for me, the job had nothing to do with Buddhist art.

At the time, Suntory's collection mostly dealt with modern painting and craft. And in regards to craft art, lacquer ware was its focal point. And it's no understatement to say that at the time, the Suntory was perhaps the busiest and most active museum in Japan. I traveled to many places, and people remember you. Acquaintances increased, and the art world started to take notice of me. And after a while, MOMA Tokyo asked me to fill a curating spot at their museum. I was headhunted.

W: So essentially, your theories on craft art were nurtured at Suntory?

K: Correct. Basically, I've always enjoyed three-dimensional art. Just like the statues of Buddha. I never was interested in paintings. To be honest, I was "forced" to study lacquer at Suntory. But it was fun, learning the art on my own. And at the Suntory, I slowly began to learn about yakimono as well. And as you well know, in regards to Japanese modern craft art, ceramics was unparalleled in terms of both quantity and quality.

W: True. The impact that ceramics had on the entire Japanese craft world is extraordinary.

K: Exactly. Especially when considering the shift from modern to contemporary, it was always ceramic art which led the way and moved forwards in breaking barriers and boundaries. And in that sense, the Suntory allowed for me to experience these movements that were sparked by ceramics, and as I began to interact more frequently with potters and their art, it was a natural progression for me to learn more about yakimono. You see, I never had a teacher who taught me yakimono. But I suppose MOMA Tokyo's 2nd Chief Curator of the Crafts Gallery, Hasebe Mitsuhiko, was the person who really influenced me in terms of how I view craft art. Although we might have had theoretical differences, Hasebe-san himself had such a graceful air to him. And when such a man says, "that is good" or "this is bad," you listen to him and think, "hmm, that might be true." It wasn't until I transferred to MOMA that I began to seriously study yakimono.

W: So you learned to hone your eye and your trade from Hasebe-san, as well as the training you had with Buddhist sculpture?

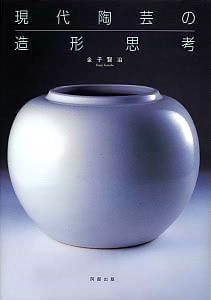

K: I suppose you can say that. I just love the exquisite proportions found in Buddhist statues. It's a balance and a proportion that is not found in in the West. And if you see the beautiful hakuji tsubo (white porcelain vase) by Tomimoto Kenkichi that I chose to grace the cover of my book, "Cognitive Formation in Contemporary Craft Art," I think you'll find a similar balance. It's a proportion that is minimalistic and refined, but with a distinct and impressive form.

Cover of Kaneko Kenji's Book

Vase by Tomimoto Kenkichi

W: If you like Tomimoto's white vases, I have a hunch you like the Tottori potter Maeta Akihiro's works as well (see a set of great Maeta yunomi at japanesepottery.com).

K: Well, his words just hit the spot. It's not that he thinks the same as me, or the fact that I mentioned a theoretical aspect to him first. Maeta said it first, and then I realized that yes, this is exactly how I feel. I think it was Maeta who helped me understand my own tastes.

(Wahei's note: readers, be keen to what Kaneko says. He just said he enjoys Maeta's words, and not his work. It appears as if Maeta's ceramic philosophy is the prime factor for evaluation, and NOT the art itself. The horse before the cart, perhaps?)

Blossoming of Ceramic Art Theory

W: How many years have you been at MOMA Tokyo?

K: It's been 20 years.

W: So that's after the untimely passing of Yagi Kazuo and Kamoda Shoji, no?

K: Right. So even though I write about them extensively in my theories, I've never had the chance to meet them in person.

W: That's quite surprising, as I've read many of your works, and you write about them as if you know exactly how they think and feel when making a work, especially in their representative works, such as Yagi's "Mr. Zamza on a Walk."

Yagi Kazuo's Mr. Zamza on a Walk

K: Well, my information is often taken from past literature, as well as from testimonies by relatives, friends, and apprentices of the artist. Even when I write about a living artist, it's very hard to extract the thoughts of an artist simply by meeting him or her once. They usually don't open up their thoughts so quickly. That's why it's important to meet the artist over a number of occasions, so that their thoughts begin to flow naturally. I can then finally begin to grasp how that person is within my head. And with that in mind, I also check what the artist writes, along with his works, letters, and testimonies from others. That way, I begin to build an image of the artist.

(Wahei's Note: Again, notice that for Kaneko-san, the works are almost ancillary to the artist, and are not the central focus when evaluating ceramic art.)

W: Interesting.

K: I wrote this in the ending to my book, but the only reason I came to MOMA Tokyo from Suntory was because the grass looked greener on the other side. I still don't know if coming to MOMA was the right decision, or if I even like what I'm doing. I suppose it takes a number of years to realize if what you did was right. And it took me 10 years until I became head of the ceramic art section of MOMA Tokyo.

W: Did you know of such artists as Tomimoto Kenkichi and Kato Tokuro before you filled that position?

K: I've heard their names before when I was at Suntory. Regarding Tomimoto, I first saw his work on a school field trip to the Ohara Museum in Kurashiki. And while I was trying to get into college, I saw his work again at MOMA Tokyo. I remembered the artist from my time at the Ohara, and pleased, I brought back a catalogue. So in that sense, I did know of potters who were famous. And while I was at the Suntory, we did have an exhibition titled "Contemporary Ceramics," produced by Hayashiya Seizo, the famed critic. At that exhibition, I first experienced Yagi Kazuo and Kumakura Junkichi (both of Sodeisha fame). And from that experience, I nurtured an unfaltering interest towards the work of Kumakura.

Piece by Kumakura Junkichi

W: So that was your first dip into the avant-garde.

K: Well, I had always thought pottery to be about vases and plates. And since I wasn't an expert, I had the freedom to like something without thinking too much about it. The way Kumakura gives life into a lump of clay had just tickled my imagination. But at the time, saying that I wanted to hold a large Kumakura retrospective brought jeers, such as "you must be out of your mind!" You see, Kumakura was hardly as recognized as Yagi, and many did not know who he was. He had become a forgotten figure, but to me, he had an enormous impact on how I perceive ceramics, and that is the reason I wanted to hold an exhibition on the artist. And also seeing Tomimoto's white vase and its beautiful form, I felt as if I had to learn the secrets behind him and his art.

W: Contemporary ceramics today is a large genre, featuring so many kinds of ceramics. The boundaries have undoubtedly expanded. Looking back, through your eyes, how would you review the 1990s? Would you call it a period of post-modernism?

K: No, I've never called it that. But before we discuss the 1990s, we must understand what the 1980s was all about. The 1980s was the Claywork movement (claywork were larger ceramic pieces that were often based on concepts, did not have functionality, and usually fitted an installation format similar to fine art). Before that was the avant-garde ceramics movement, primarily featuring the works of the Sodeisha. But when looking at the claywork movement, the term itself really didn't mean anything at all. Someone just came around and said, "hey, yakimono is looking a bit different than before, so let's plug a name onto it." But the essence of the yakimono was no different from the 1970s and the 1980s, only that the size of the works became much larger. It's like the Japanese word for "slacks." People in the old days used to call slacks "zubon," but now the word has changed to "pantsu." Two different words that mean the same thing.

In the 1960s, the Sodeisha built the foundations for the concept of selecting and focusing on a single material, in their case clay, and transforming it through basic forming techniques. This was expanded in the 1970s. In the 1980s, many artists claimed that they too were selecting and focusing on a particular material, but what they actually made were works that had nothing to do with the material itself. This is my "principle of material relativity." (素材相対主義). So in other words, if it's made of clay, anything goes! To fire it or to not fire it, to use clay as a material for industry, to use clay as a material for sculpture, to use clay as a material for craft. All these uses for clay were lined up and piled together as comprising this vague notion called "claywork theory."

The 1990s, thus, was the antithesis of this movement, or in other words, a return to the question of clay. What does it mean to form in clay: individual potters took it upon themselves to discover and reevaluate what clay meant. On the surface, or just by looking at the works made by artists in the 1990s, things may not appear any different; but while the economic bubble was bursting, the ceramists of Japan were moving toward a return to clay and what it meant to make ceramic art. More explicitly, a return to clay means making works that can only be made through the use of clay, and not through any other material. Such were the 1990s.

W: Hmm. In the 80's, artists such as Akiyama Yo started to make a name for themselves. But he was grouped together as part of the claywork movement. But I have to say, his concepts and his reverence towards clay has probably not changed at all from the 80's to the 90's. In other words, Akiyama was making works in the 80's with the same conceptualism as how you just explained the 90's.

K: My sentiments exactly.

Crafts Gallery, MOMA Tokyo

W: Sugiura Yasuyoshi, as well, places sincere and heartfelt emphasis on what it means to work in clay. But he was also labeled a claywork artist. Sugiura made a name for himself in the 1980s, and his work in the 1990s still carried the same concepts as he first made in the 80s. But if this is the case, then wouldn't the existence of these two artists directly contradict how you differentiated the 1980's from the 1990's? Of course, artists such as Nakamura Kinpei and Nishimura Yohei might fall into your explanation of the the 80's.

K: Actually, what I just said might be hard to visualize in regards to ceramics, But take the craft of textiles, for example. The 1980s tried to encompass the fabrics made by industrial mass production with the works of artists who made fabrics as a form of art. In regards to ceramics, some artists believed they were making fine art, and just happened to use clay as their medium. On the other hand, there were artists who purposively and uniquely selected clay as a material in order to realize their theories of formation and self-expression. These are two different cognitive processes that are taking place, but the term "claywork" happens to unjustly group them together. This was the 1980s.

So when we speak of Akiyama-san or Sugiura-san, you are right to say that there were those special artists who exclusively used clay, as clay was their raison d'etre for making art. But there were a large number of artists who didn't think like that. Yet the two spectrums were lumped together in one large family. And if such a peculiar and unsatisfactory situation were left unchanged, I think it would be extremely difficult to discern which artists think one way or the other. Yakimono becomes inexplicable. That's why it was my intention to pick up artists who use clay as a form of "cognitive formation" and not that of fine art. "Oh, he uses clay, so he must be part of the claywork movement" should not become standardized thought. If it did, it would be a funny predicament we would find ourselves in. I think a lot of people, artists included, were deceived by the term itself.

W: I think you're right in saying that a sense of confusion could be seen at the time.

K: It's probably around 1993 when the perception started changing. The ceramic art theory of the 1980s started to sway off course, and to put an end to the claywork movement and to put a proper assessment of yakimono theory, a countermovement began to take place in the early 1990s.

W: Or more specifically, the arrival of Kaneko Kenji to the ceramic scene in 1993 was the impetus for change.

K: Oh no, I had arrived a bit earlier than that! (laughter) But you know, at the time, if someone didn't use the term claywork, they would be ostracized from the mainstream. I was criticized for being "backward" or being "a country bum."

Craftical Formation Theory

W: So, the theory you call Craftical Formation 工芸的造形論 was first published in 1993?

K: I think I began to use the term around 1991. No, perhaps 1990. And the central gist of my theories have yet to change since this time. The words themselves have changed, however, such as "principle of material relativity" or "craftical formation." The latter phrase, for example, was first used by Nakamura Kinpei and Sekishima Toshiko. When I first heard it, it didn't do too much for me, but as I began hearing it more often, I realized that this was the term I wanted to use.

W: I had always assumed that it was you who devised the term.

K: Oh no, it was Kinpei-san, but he was using it without much thought. Of course, it's an invented phrase, and the English translation "craftical formation" is an invented word as well.

W: I had no clue as to what "craftical" meant when I first read an English translation of your work, Kaneko-san. I think "craft-esque" will be still easier to understand.

K: Really? I think I'll use that from now on. (laughter)

W: This term is a bit complicated. You call it "craftical" or "craft-esque" formation. So does that mean that a ceramic work is no longer craft if it fits into your theory? In other words, the term seems to emphasize "formation" as central, rather than focusing on craft.

K: To put it bluntly, there are two ways of forming something. On one hand, you have an image in your head, and to materialize that image, you choose a material to work with. On the other hand, you start with a material, and then begin to instill an image or concept within the material. The latter is craft-esque formation, while the former is fine art. Many things fall under craft-esque formation. Sculptural craft, avant-garde craft, traditional craft, etc, as long as the material comes first. In regards to ceramics, clay must come first.

W: I actually understood what you just said! So you're saying that your theory does not partition the avant-garde from the traditional.

K: Right. I think there's a middle road that encompasses both of these elements. But what is fundamental is the fact that the artist is bound by the material he or she uses, and with that material, he or she instills creativity and concepts. If the concepts come first, the material becomes ancillary, or second to the concept. This, then, is fine art.

W: That middle road, then, might be analogous to how Japan had traditionally perceived art. It's because Western ideas came into Japan during the Meiji period at which the separation of fine art and craft became extreme.

K: Exactly. But the problem is that if there isn't a fusion between traditionally Japanese sensibilities and the sensibilities of the West (esp. in regards to art as a means of self-expression), the craft art we have today will just be labeled "industrial art." Because no one tried to combine Western and Japanese notions of art, we see in the West the sorry state of separating the "functional" from the "sculptural." The first to achieve this needed amalgamation

of principles were the members of the Sodeisha.

Clay is terribly ill-adapted for making serious sculpture. It's much better to use bronze or marble or some other material. So if someone is trying to make "sculpture" through clay, the concept comes before the material. But if someone works with clay and happens to make something nonfunctional or sculptural as a means of self-expression, than this is craftical formation.

It can't be "from concept to clay."

It has to be "from clay, comes concept."

W: I'm a bit reassured by what you just said, Kaneko-san. You're not trying to push ceramic art into something that is equal or superior to fine art. You are trying to make a new path for ceramic art.

K: Craftical formation is not quite fine art, nor is it quite craft art. It's somewhere in between. We see today, not only in ceramics but in weaving, dyeing, bamboo, metalwork, lacquerware and wood craft a shift in how craft artists perceive their materials. But what do we call that? I tried to think of an explanation, and I ended up with craftical formation. Or craft-esque formation. In this regard, I think the "craft" artists of Japan have a far greater advantage than the craft artists of Europe or America. In those countries, craft was always considered a simple industry, while in Japan, craft was considered at a level similar to fine art. Because Japan has had this tradition of respecting craftsmen and their craft, along with Japan's long and storied history of using various materials and techniques, that we find ourselves in the highly creative and energetic state of Japanese ceramics today.

W: And true enough, today's Japanese ceramics is receiving great praise the world over. The international interest in Japanese pottery is probably at its highest ever, and this interest is leaning towards contemporary pottery, without differentiating the functional from the nonfunctional. Avant-garde or traditional, whatever. The quality of ceramics is top-class, and museums and art collectors are tuning in.

K: I agree. I think the number of collectors and gallery owners who visit Japan to buy ceramics is much higher than it was before. I think it is evidence of the fact that the West is changing the way they perceive ceramics. It's not "why are you doing craft, of all things?" anymore. It's something larger, greater, and more dynamic than it's ever been, and this is largely due to the emergence of the Sodeisha in the 60's. They shattered the conceptions of craft which were looming large in Europe and other Western nations. And today, I think the West is wanting its very own "Sodeisha" movement to jump start a new wave of ceramics.

W: Perhaps this sea change is born from you, Kaneko-san.

K: Well, I wouldn't take all the credit. (laughter) But I'm pretty sure that a few are listening to what I say.

As I translated his interview, I've begun to think that Kaneko might be on to something. We can shrug him off as merely intellectualizing ceramic art, and muddying the waters, if you will. But on the other hand, I find it hard to deny the fact that changes in how we perceive art often do not stem exclusively from art alone. In a world where fans, critics, media, artists and their art ALL join hands, is a world where paradigms shift and movements are made. In other words, whether you like it or not, we're all in this together. We influence one another. And then, we move forwards.

Kaneko is merely, from his point of view, trying to create a new path for ceramic art to take, for ceramics itself is far different from what it was in the Momoyama period. Just a word of caution, however. If he's trying to make new theories for the sake of vindicating his own ambitions, then I believe Japan is in need of someone to take a stand against Kaneko, as he is slowly but surely flexing his muscle to the point where he has gone unquestioned and unchallenged.

And if he is doing it because he sincerely loves ceramics and the yakimono society, and that his theories will better Japanese ceramics as a whole, I only wish him well.

But this, in no way, means that I will be walking with him.

End interview with Kaneko Kenji

Interview & story by Aoyama Wahei

written for yakimono.net & e-yakimono.net

INDEX TO

ALL STORIES

by Aoyama Wahei

|