|

Maverick Tokuro

Unearths Ceramic Truths

By ROBERT YELLIN

for The Japan Times, September 13, 1997

To celebrate the centennial of the birth of the grand Seto potter, Kato Tokuro (1898-1985), the Ishikawa Prefectural Museum in Kanazawa is hosting an exhibition showing 160 of Tokuro's Showa masterpieces (in 1997). The last time a large exhibition of Kato's works travelled Japan was in 1984 when his work was shown side by side Momoyama-era (1568-1603) Mino wares.

Tokuro was born in Seto city in Aichi prefecture, an ancient potting center that is one of so-called Six Old Kilns of Japan. At the age of eight he began collecting potsherds from old kiln sites; he took over his family kiln in 1914 when he was only 16.

His imagination sparked by those fragmented Mino clay chips he had collected, he set out on a course to reproduce those classical Mino styles, which include Shino, Setoguro (Black Seto), Ki-Seto (Yellow Seto), and Oribe wares.

After years of studying the Momoyama Mino shards for clues on glazes and firing, he made the chawan (teabowl) -- called "Tsurara" (icicle) in Showa Year 5 (1930), which received much attention from the then very stiff and closed society of pre-World War ll Japan.

In 1933 he published a book on Ki-Seto ware, questioning the long held belief that Ki-Seto was fired in Seto. Tokuro put forth that Ki-Seto was actually fired in and around Tajimi-city, Gifu prefecture (he has since been proven correct). This "slander" against the ancestors of Seto led to the infamous Ki-Seto book burning incident the same year.

Another anecdote about Tokuro is probably the greatest potting scandal of twentieth century Japan known as the Einin no Tsubo Scandal. Tokuro prided himself on his ability to reproduce classical pieces so well that not even the experts could tell them apart. To prove his point, in 1937 he made several replicas of Einin period (1293-1299) Heishi, an old Seto sake bottle. It's not clear exactly when, but he broke a few of the pots and buried the shards along with an intact heishi in a medieval kiln site and had them "discovered" during an excavation of the kiln in 1960. (Many say that it was actually Kato's son Okabe Mineo who made the reproductions)

The well-known ceramic authority Fujio Koyama (1900-1975),a friend of Kato's who was on the committee that decided matters of cultural importance, proposed that the recently found heishi be designated as an Important Cultural Property. Kato then revealed his prank to a fuming Koyama who would not believe Kato based on the evidence of the shards. Kato broke that news to a fuming Koyama as well. He had duped the experts, but nonetheless it caused great embarrassment to all involved and both Koyama and Kato resigned from their respective official positions.

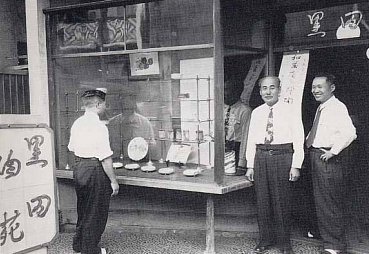

Kato Tokura (middle) outside the famous Kuroda gallery shop

"When you set your work in the public eye, you get scathing criticism. That is when you become a mature person," Kato wrote about these incidents. Withdrawing from public life, he changed his ceramic signature to "Ichimusai" (meaning "one nothingness-purity") and again devoted himself to the making of tea utensils and toheki (ceramic walls).

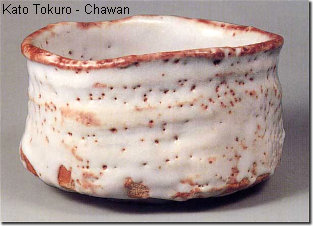

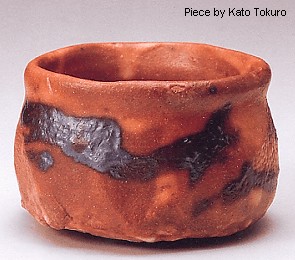

His chawan, mostly Shino, Ki-Seto, and Setoguro, are gracefully powerful and at the same time reflect Kato's deep Zen beliefs.

Daisetsu Suzuki, the great Zen scholar, refers to the term jiriki, which is salvation through one's own labor. Kato did just that. Wearing his jeans overalls and straw hat, he would walk in the mountains looking for old kilns and good clay, thus he was given the nickname of "No no tojin" (country-bumpkin potter). He referred to himself as a "being like a worm" in that he always tasted the clay he found. "Good clay tastes good," he was fond of saying.

For his Shino chawan the clay was paramount, followed by the firing. He said of chawan, "They are not only to gaze upon, but must be held and used to appreciate the inherent beauty and art; this cannot be done either with paintings or sculpture. To make a good chawan, first one has to understand the value of old masterpieces. I have come to that understanding but still can't seem to make even one worthy chawan!"

He certainly had a sense of humor. His Shino chawan are arguably the finest ever made since the Momoyama period. Take for instance his chawan named Ryujo that shows the pure white warmth of the thick feldspar Shino glaze. Underglaze iron brush marks can be seen through the translucent glaze. The voluminous rounded form has a thick flared drinking lip.

Kato used to refer to his chawan as being like castles and that they are; monumental, yet unlike a castle, they can be held in the hands. Collectors and critics agree that his best chawan were made during his early seventies.

In addition to the already mentioned Ki-Seto book, he authored a major dictionary of ceramics that was issued in volumes beginning in 1934 and was collected in one volume and published in 1972 under the title "Genshoku Toki Dai Jiten" and to this day stands alone as a reference for any oriental ceramics student or collector.

From Seibu Department Store Exhibition

Ironically, in 1952, his Oribe ware, instead of his Shino, was designated as an Intangible Cultural Property -- meaning the technique and not the person. Kato was never designated a Living National Treasure. The Suishoen Togei Memorial museum in Nagoya is devoted to Kato's work.

Copyright

The Japan Times, September 13, 1997

LEARN MORE ABOUT THIS ARTIST

|