|

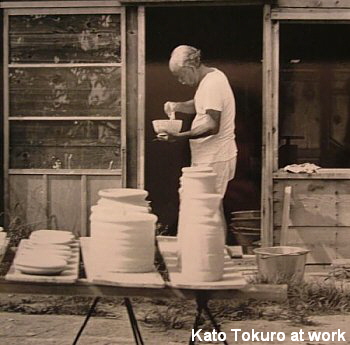

Shirasu Masako and Kato Tokuro

Between Lies and Truth

I hope all of you are having a beautiful holiday season.

I personally took a few days off of work to visit Kyoto (my fourth time this year). As I was taking a stroll around Kodaiji Temple (the resting place of Toyotomi Hideyoshi's wife Nene), I quite unexpectedly ran into a Koro (incense burner) exhibition in the temple compound. Amused, I was even more surprised to find that the works exhibited were by the likes of Kiyomizu Rokubei 5th, 6th, and 8th, Kusube Yaichi, Rosanjin, Tomimoto Kenkichi, Kondo Yuzo, Itaya Hazan, and Shimizu Uichi. A tremendous list, many of these names you might remember from my last two articles. Talk about coincidence. It seemed as if I was lured to these works by some unknown force.

In reverence, a short obituary comes first.

Living National Treasure Kinjo Jiro (Important Intangible Cultural Property holder for Okinawan ceramics) passed away at the grand old age of 92 due to heart failure, December 24th, 2004. Born in Okinawa in 1911 (although his parents didn't register his birth until a year later, hence the official birthdate of 1912), Kinjo began pottery at the age of 13. At age 26, Mingei philosopher Yanagi Soetsu and potter Hamada Shoji "discovered" Kinjo upon their visit to Okinawa, and felt great mutuality between his works and the ideals they were expounding at the time. Kinjo excelled at glazing, eching, hakeme (white slip brush strokes) and the potter's wheel, and was designated an IICP holder in 1985. Kinjo was a humble and quiet man, who resented being called "sensei," always thought of himself as a craftsman, not an artist. This utmost humility lives on in his work.

This week., I wish to translate a short Japanese essay written by Shirasu Masako (1910-1998) for the magazine Taiyo on the life of Seto great Kato Tokuro. Shirasu (1910-1998) was a famed collector, critic and writer on Japanese pottery and aesthetics, and was regarded by many to have had the greatest eye of her generation.

I chose this particular essay because I felt Shirasu captured the enigmatic complexity behind Tokuro (1898-1985). Shirasu's language is at once tart and brisk, lucid but vague, elegant but harsh. Like Tokuro, she uses simple but metaphoric words to show us elements of Tokuro, while in no way attempting to conquer or reconstruct the man. This technique, I think, does better to elucidate Kato Tokuro, in a far more caring and intelligent manner, than some of her contemporaries. I find it a precious resource, and wish to share to fans of Tokuro another insight into a potter who enchanted us all.

Between Lies and Truth

Written by Shirasu Masako

for Bessatsu Taiyo, 1996, Heibonsha Publishing

Translated by Aoyama Wahei

I knew Tokuro-san from long ago, and would sometimes dine with him and Aoyama Jiro, or would go with them to Matsunaga Yasuzaemon's tea ceremony. I would also drop by his exhibitions, but as I quickly became involved in antiques, I did not bother to buy his works. When I later realized, his works had become more and more expensive. In any event, his Shino were, without question, wonderful.

|

Shino Guinomi

by Kato Tokuro

|

|

Come over, come over, Tokuro would always say to me, and as there were talks of making a book from our conversations, I would go over to meet him in Nagoya. This was in the early 1970s. But even when I did go, there would hardly be dialogue, as Tokuro would drink himself silly. Tokuro would drink faster than me, and as his pitch of consumption increased, he became so inebriated that I could not comprehend what he was saying. This may also be because I never enjoyed talking to him. You see, I could never tell if what he said was fact or fiction. If I would see him nine times, he would only give me six.

As I knew I would drink with Tokuro, one day I brought along a Shino guinomi. When he saw it, Tokuro said, "This guinomi is fit for the likes of Tokuro. It's a shame that it will be left in your hands." The guinomi was actually a thinly formed mukozuke (small bowl) that I had purchased at Kochukyo (the famed Ginza antique store), with a wonderful color and was easy to drink from. I retorted, "The man named Kato Tokuro can make his own Shino. Go along now, make one for yourself."

His wife was a gentle woman with the face of Ebisu (one of Japan's Seven Lucky Gods), a countrywoman straight from the fields. She would always smile with understanding approval at whatever Tokuro said, a good wife like none other. Tokuro would say that she gave birth to nine children, but the truth behind this, I do not know. Yet nevertheless, Tokuro's wife was the true pillar that held the child-like Tokuro up from the shadows.

His workshop was originally a small factory for processing fishcakes, and it really did look like a laboratory. For someone like me, who had seen Rosanjin's and Arakawa Toyozo's workshops, this came as quite a surprise. Both Tokuro's house and his kiln were also, like factories, bare. This man doesn't care for anything other than his work, I thought. In his house were rows of unfired chawan (teabowls), all made by hand pinching. He said that he just made them to warm up; like dancing, it is important to hit a rhythm and find a stride. He then said he only fires the good ones, but again, I could not discern the truth.

|

Tokuro was an actor, ready to melodramatically shatter teabowls pulled straight from his kiln with a flair that was at once so natural, yet contrived. He was brilliant on television as well. Only a genuine liar could pull it off, I thought. He would tell me, "I give the perception of seriousness on the outside, but down below, I pull some strings." I've never seen another person slip between truth and lies with greater ease. But then again, that's what made him captivating.

It's because he put his hand into something like the Einin Tsubo that left Tokuro without any awards or titles. It made him the perpetual outsider, but in retrospect, this was better for him. Even before the Incident, I had gone to Hakuzan Shrine to see the Kamakura period work called "Honka." You could not blame anyone for believing the Einin Tsubo to be the real thing, as it was so very well-made; one could hardly tell which was the real thing. A great number of people in Seto despised Tokuro for his actions, but I think such peoples' views are myopic. You have to admit what is good as good.

One's personality comes out in yakimono (literally "fired thing"). It is called one's soul, and without soul, I don't think you can truly call a work yakimono. To give a stark example, Rosanjin had great technique and an excellent brush. But I can't feel the presence of soul, as he was a man who curried the favor of his clientele. In that regard, Tokuro-san was one step above Rosanjin. And Tokuro-san could write the most splendid of calligraphy.

Tokuro-san was a true craftsman. Those that make works with an ego, thinking themselves to be artists, do not make good things. Tokuro-san was, without a doubt, an artist, but the way he perceived himself was with the soul of a craftsman. Both the authors Nagai Tatsuo and Kobayashi Hideo thought of themselves as craftsmen, not artists. Those that create are all, essentially, craftsmen. Rosanjin was like a producer, but Tokuro-san made his works from start to finish. He used to say that the amount of clay he'd accumulated could last his family for two more generations. I wonder if this is true.

(Wahei's note: Tokuro's 3rd son Shigetaka uses his father's clay today, along with Shigetaka's son Takahiro. Hence, Tokuro would be pleased to find that his family is indeed using his clay for two generations after his passing).

Tokuro-san began his career making perfect, faithful copies of Momoyama masterpieces. They were all good. You see, a craftsman who does not copy is no good. It is when the craftsman truthfully masters the art of copying, that he can finally nurture his own individuality within his work. And with Tokuro's works, one has to admit that they are undeniably his. But one work that I must say I do not regard highly is his purple Shino chawan "Murasaki Nioi" (Scent of Violet). It looked dirty, with no inkling of charm. It did not have crispness or grace.

As I was making fabrics in Ginza, Tokuro-san would ask me to make white shifuku (silk pouches) for his purple chawan. Even at that time, I always thought of them as failures. Some chap seemed to have coined a nice name onto the vile things. But Tokuro-san was a man who, if praised, would be so happy that he'd go out and show that he can do it all over again. I don't know how many Murasaki-Nioi he eventually made, but they were all terrible. But nonetheless, Tokuro already had enormous name value at this time, and customers with no "eye" would jump at his name, rather than see the works for what they really were. I told Tokuro, "These are utterly boring. You can do better, and I find it sincerely regrettable that you don't." Tokuro-san looked quite perplexed at this criticism, but would laugh heartedly and shrug it off. Tokuro, at this point in time, did not care for saving face.

Individuality derives from standing on the shoulders of tradition. By acknowledging the roads taken, by understanding history, we can finally arrive at discovering ourselves. By first understanding how to make something, it is our next duty to take it one step further. Even in the art of Noh (Japanese traditional theater), the most minute of details have been passed down in the form of procedural kata. Yet only when an actor masters the traditions, can he finally break free and turn them into his own. Those that simply follow what the "kata" formalities of tradition have taught them, will forever only be "kata" themselves. In the end, they will realize that they had not understood a thing.

In other words, only those who have fully grasped the "kata" can be free. They can then embark in making their own art. In that regard, we should be grateful for the "kata." In Noh, one finally masters the art after the age of 70. Pottery requires more strength, and thus to become a "real" potter, the age of 50 must be passed. In other words, only those who have fully grasped the "kata" can be free. They can then embark in making their own art. In that regard, we should be grateful for the "kata." In Noh, one finally masters the art after the age of 70. Pottery requires more strength, and thus to become a "real" potter, the age of 50 must be passed.

"You're running too hard," Tokuro-san once told me. How perceptive, I thought, as at the time I was running as busily as the god Idaten. And as I started slowing down due to age, I finally could see the truth, and see what was truly beautiful. We can consider the Murasaki-Nioi as a bad joke. But when one sees how many beautiful things this artist has left behind, it leaves me with the impression that I have nothing more to say to Tokuro-san. The body is an ephemeral thing, so let it die. I have nothing left to say, nor do I have anything left to ask this man. This is the end.

Written by Shirasu Masako

Bessatsu Taiyo 1996

Heibonsha Publishing

Translated by Aoyama Wahei

Shirasu Masako, along with her teachers Aoyama Jiro and Kobayashi Hideo, were tremendously colorful characters that were symbols of a golden era in the Japanese appreciation of its own culture. I hope the interest in her life and in her writings will only grow as the years pass.

Regarding the Einin Tsubo, it is a goal of mine to someday write a full-fledged series on the topic, as it is an extremely complex and important part of modern ceramic history, ending in Koyama Fujio's and Kato Tokuro's fall from grace, and the parting of ways between father Tokuro and son Okabe (Kato) Mineo. Let's hope the time will be right next year.

Furthermore, I have just finished translating a small volume for the Modern Museum of Art, Tokyo. It is a comprehensive introduction to Japanese crafts, from the traditional to the avant-garde. Japanese craft fields such as ceramics, bamboo craft, metalwork, glasswork, lacquerware and dyed/weaved fabrics are contained therein. I find it a valuable reference material to those interested in Japanese studio crafts since the mid-19th century (modern) to the present (contemporary), filled with names, dates, and photos, in both Japanese and English, written by some of the top scholars today, such as Kaneko Kenji, Chief Curator for MOMA Tokyo (whom I will be also interviewing next week. (Will Wahei fall prey to his intellect, or will he be able to hold his own and challenge the ideas of a man who greatly influences ceramic art history with a wave of his pen? The excitement bubbles.) I'll put out a notice on this column once the MOMA book comes out in March, and will try to deliver some excerpts from it as well.

I've also recently interviewed such potters as Kamada Koji, Isezaki Koichiro and Tsujimura Yui for the Japanese version of this site. For those who can read Japanese and are curious to know more about the above potters, please visit the links below. For the January issue, I've interviewed the important ceramic artist Sugiura Yasuyoshi (a truly thought-provoking discussion ensued), and will be out in early January.

- Interview Tsujimura Yui (Japanese language; outside link)

- Story About Tsujimura Yui (English language)

- Also in Japanese is a provocative discussion on aesthetics with Tsukada Haruyoshi, the owner of Gallery Mukyo in Ginza (Japanese language; outside link). For English story about Gallery Mukyo, click here.

On that note, the next update of Japan Ceramics Now will be published next week / year.

良いお年をお過ごしください。(Please have a wonderful new year)

by Aoyama Wahei

|