|

MOMOYAMA REVIVAL

Pottery worth giving it all up for

By ROBERT YELLIN

for The Japan Times, Oct. 9, 2002

|

|

|

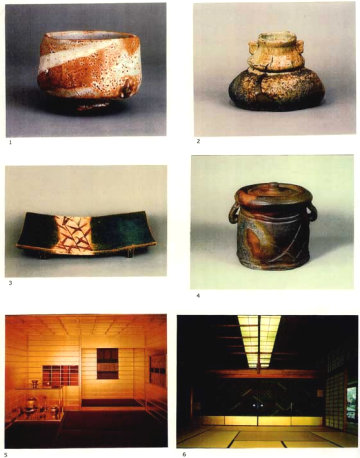

Clockwise from bottom: Bizen ware mizusashi and triangular vase with a row of bosses, both by Kaneshige Toyo; "Bag of Desire," a mizusashi by Handeishi Kawakita

|

|

|

Say the word "Momoyama" to any Japanese pottery connoisseurs, and their eyes will inevitably light up. Most ceramic enthusiasts would give up any Saturday-night vice to own just one Momoyama Shino, Bizen or Karatsu guinomi (sake cup) or chawan (tea bowl).

Allow me to explain. Many of Japan's greatest pottery styles (and other art forms) matured under those who shaped the cultural landscape of the Momoyama Period (1568-1715). Most of these artistic "directors" were powerful warlords and Zen monks connected to the Way of Tea. These men forsook expensive imported Chinese items to focus on humble-yet-sublime native pieces and Korean wares.

These tea wares, however, lost much of their popularity in the colorful Edo Period (1603-1867) through to the Taisho Era (1912-1926). It wasn't until a Momoyama revival occurred in the early Showa Era (1926-1989) that these treasured wares were again appreciated for the glory and pride they have given to Japan's splendid ceramic heritage.

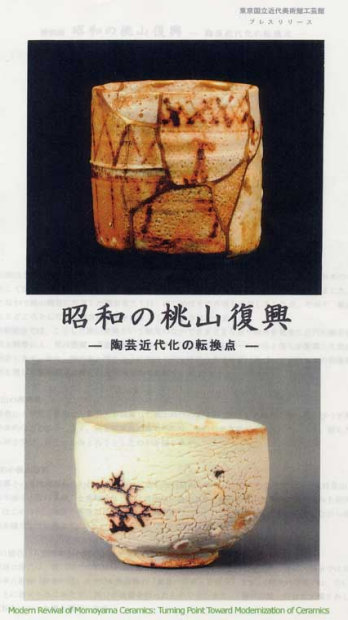

A look at how all this unfolded is now on at the National Museum of Modern Art, Crafts Gallery in Tokyo, in a restrained exhibition titled "Modern Revival of Momoyama Ceramics: Turning Point Toward Modernization of Ceramics." Click here to see the exhibit's promotional flyer.

That turning point began in the 1930s, led by a handful of regional potters. Those represented in this exhibition include:

- Toyo Kaneshige (1896-1967) from Bizen

- Hagi's Kyuwa Miwa (1895-1981)

- Handeishi Kawakita (1878-1963) in Mie

- Rosanjin Kitaoji's (1883-1959) Kamakura kiln

- Toyozo Arakawa (1894-1985), whose studio was in the hills of Toki, Gifu Prefecture

Turning away from the then-current craze for Chinese wares (ironically similar to that which usurped appreciation of Momoyama ceramics centuries before), these men revitalized the traditions of Momoyama Period wares.

|

|

|

Piece by Arakawa.

For more on this

artist, click here

Piece not shown

at exhibition

|

|

For Arakawa, it all began with a fateful encounter with a chawan and the excavation of a single shard. As he tells it in Janet Barriskill's book Visiting the Mino Kilns:

"My thoughts go back to that time in the fourth month of the fifth year of Showa [April 1930] when I discovered the ruins of the old kiln at Ogaya; it was at the time of the Nagoya exhibition by the Hoshigaoka kiln of Kitaoji Rosanjin. In Nagoya, I had the opportunity to see a cylindrical teabowl -- decorated with a bamboo shoot -- owned by the Sekido family. On the base of this teabowl featuring a bamboo-shoot motif drawn with the utmost simplicity, I could clearly see a red fire-colored mark on the area where the hamagoro [circular pad of fireclay used to separate the pot from the sagger during firing] had been placed. Looking closely, I noticed a small piece of clay adhering to this area; it was decidedly red in color. Up until then it was commonly thought that this pot had been fired at the Seto kilns, but to me, this did not appear to be Seto clay. So where did this clay come from?"

Arakawa knew that in the hills outside Toki, there was clay of the color he had seen. So the next day he trekked out to the old Momoyama kiln sites and excavated a shard with the exact same motif as the Sekido teabowl. Up until that time, Shino and other Mino-style wares (such as Oribe and Ki-Seto) were thought to have been fired in Seto.

|

Arakawa's discovery rewrote Mino's ceramic history. Never since has a fragment bearing a bamboo-motif been uncovered, and that very important shard is on display in the current exhibition, along with 16 Arakawa masterpieces not often displayed.

There are also a few glorious Shino chawan with citron-pitted surfaces and "landscape" patterns known as ishihaze formed when small stones in the clay burst to the surface during firing. One Arakawa Shino chawan shows, in underglaze iron designs, a bamboo shoot painted in homage to the Momoyama chawan that Arakawa held on that spring day in 1930, and to its unknown maker.

Kaneshige was responsible for rediscovering the method of processing clay, making kilns, and loading and firing them the Momoyama way. Bizen clay in the 1930s was shiny, like bronze and used mostly for ornamental figures called saikumono. Kaneshige was a saikumono master, yet abandoned that road in search of the shibui Momoyama Bizen that was made by his ancestors. We see the stunning results in 13 Kaneshige works on display. One is a slouched-over mizusashi (freshwater jar) that looks like a leather bag, while a more rugged mizusashi has all the classical firing characteristics of Momoyama Bizen: rich "clay flavor," rough patches of crusty ash, "sesame" drips (red-pine ash fusing and melting on a pot, remindful of ground sesame paste) and bold yet subdued incised carvings. These can also be seen on his masterpiece vase made in 1953 -- it is a monumental work.

Handeishi Kawakita is the odd man out here, as he was a wealthy banker-turned-potter who worked exclusively in tea wares. Kawakita referred to himself as an amateur, and his works do lack technical proficiency, but they are in keeping with an "amateur tradition" that dates back to the great Koetsu Honami (1558-1637). His chawan have charming personalities and quirky rhythms about them, bearing names such as "The Wealthy" or "Thin Ice"; Kawakita was well-known for the unusual names he bestowed on his works.

Some pieces are restored with gold lacquer, while others have been repaired with pot fragments; uniting all of the 10 chawan on display is the sense of a man at play. The piece de resistance, though, is his Iga "Bag of Desire" mizusashi (see photo at top of page), with its bulging crusty base, deep creviced body and elegantly lacquer-repaired "river." It's a piece that pays its respects to the most famous of all Momoyama Iga mizusashi, named "Yabure-bukuro (Broken Pouch)," now in the collection of the Goto Art Museum. Some pieces are restored with gold lacquer, while others have been repaired with pot fragments; uniting all of the 10 chawan on display is the sense of a man at play. The piece de resistance, though, is his Iga "Bag of Desire" mizusashi (see photo at top of page), with its bulging crusty base, deep creviced body and elegantly lacquer-repaired "river." It's a piece that pays its respects to the most famous of all Momoyama Iga mizusashi, named "Yabure-bukuro (Broken Pouch)," now in the collection of the Goto Art Museum.

Rosanjin would be livid with me for not writing anything about his work -- his ego and temper are legendary -- yet he already has a fine book about him in English! So I shall allow visitors to rediscover his genius and association with Momoyama works on their own. That can be done after a stroll through the first room of about 20 actual Momoyama works. Rosanjin can be found in a room near the end of the exhibit. He is possibly fuming in his grave at being given a place in the back, yet I'm sure he'd be mighty proud to see how the greatness of Momoyama wares still inspires so many artists even today, just as it did in his time.

"Modern Revival of Momoyama Ceramics: Turning Point Toward Modernization of Ceramics" runs till Nov. 24, 2002, at the Crafts Gallery, National Museum of Contemporary Art, Kitanomaru Park, Tokyo. 10 a.m. to 5 p.m.; closed Monday. Admission 630 yen. Click here to see the exhibit's promotional flyer, which shows some wonderful pieces from the exhibition.

The Japan Times: Oct. 9, 2002

(C) All rights reserved

LEARN MORE ABOUT MOMOYAMA AND ABOVE ARTISTS

Magic of Momoyama Mino

e-yakimono.net/html/mino-momoyama-jt.html

Miwa Kyuwa (1895-1981)

e-yakimono.net/html/miwa-kyusetsu-xi-jt.html

Arakawa Toyozo (1894-1985)

e-yakimono.net/html/arakawa-toyozo.html

PROMOTIONAL FLYER FOR EXHIBITION

Modern Revival of Momoyama Ceramics

Turning Point Toward Modernization of Ceramics

About 100 works will be exhibited, including pieces by Arakawa Toyozo, Ishiguro Munemaro, Kato Hajime, Kawakita Handeishi, Kitaoji Rosanjin, Nakazato Muan, Nagano Tetsushi, Horiguchi Sutemi, Miwa Kyuwa, and Mizuno Guto.

From September 28 thru November 24, 2002

At the Crafts Gallery, The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo

Closed Monday except Oct. 14 and Nov. 4; Closed Tuesday Oct. 15 and Nov. 5

Tokyo-to, Chiyoda-ku, Kitanomaru Koen 1-1

TEL: 03-5777-8600

|