|

Part Two

Sugiura Yasuyoshi

In Clay, A Flower Blooms

Skip intro & jump directly to Part Two

For part one, click here.

I had traveled to Kyoto last Wednesday in order to accomplish two things.

My first reason was to review the new exhibition by potter Kondo Takahiro (1958 - ). Takahiro is the grandson of Kondo Yuzo, the legendary sometsuke (cobalt blue underglazed porcelain) potter and Living National Treasure. Takahiro has made a name for himself with a unique indigo blue glaze over porcelain, as well as by developing an original silver glaze that looks like raindrops over a porcelain body. Now back from studying abroad in Scotland, Kondo is currently experimenting in a unique combination between porcelain and glass.

He first exhibited this new style at the Yufuku Gallery in Tokyo last year. Yet at this first debut, Kondo had yet to fully realize his new aesthetic, and his works suffered from a lack of vitality. In other words, they were just a mix between glass and porcelain, without a striking reason for the peculiar amalgamation. They were, in a sense, just experimental. To put it even more bluntly, you could not see why he was using clay in the first place, as glass overtook clay as the prime material in many of the works. He could have called himself a glass artist, rather than a potter, and none would have disagreed. But granted, it was a bold step, nonetheless.

|

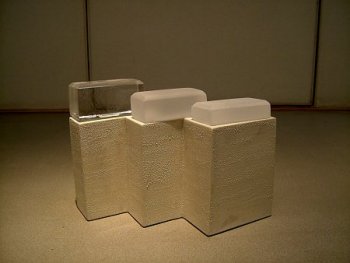

Above and Below: Work by Kondo Takahiro

|

At this new exhibition, Kondo seems to have found his stride. Successfully, he has reached a harmonious balance between the two materials. And what's more, the glass was used to merely accentuate clay, rather than trying to overcome clay. I was thrilled to find some spectacular works, with a great rhythm between glass, porcelain, and silver glazing. More on Kondo in my next article.

My second reason was to meet a young Kyoto potter by the name of Nishida Jun (1977 - ). First, I ask that all of you write down his name immediately, and keep it safe so that you won't forget. Upon meeting him at Kyoto Seika University (his alma mater and his current workplace), my convictions were affirmed. Nishida is the future of Japanese ceramics. He has taken pottery and turned it upside down, much like how Koie Ryoji did in the 70's. Koie, among other things, questioned the concept of firing. Nishida, on the other hand, has taken the concept of glazing and added a twist: just when does clay stop, and glaze begin?

A few words of intrigue.

Think powdered clay. Think powdered glaze. Think white. Think massive pieces. Think firing a piece that shatters kilns. Think 1250 degrees Celsius. Think kiln-effects. Think lots and lots of glaze. Think the weight of 1000 kilos. Think digging to find a work inside a work. Think nature. Think power. Think creativity. Think creation. Think deconstruction. Think the most genuine, sincere, and polite of people I've had the pleasure of meeting in a long, long time. Think Nishida Jun. He will only get better. (Think February too, as that's when I'll write about him.)

Closeup of work by Nishida Jun

This week, I will introduce the last installment of my Japanese interview with Sugiura Yasuyoshi (1949 - ), an extremely influential conceptual potter who had been at the forefront of the conceptual scene since the 80's. In this week's segment, Sugiura-san talks more about his own works, his feelings toward clay, and his thoughts on being a potter (unlike the last segment, which dealt more with the current pottery scene itself). Whether you agree with him or not, one cannot question his sincerity towards clay, a trademark that cannot be applied to other conceptual potters (such as Nakamura Kimpei or Kiyomizu Rokubei 8th).

Nishida Jun. Kondo Takahiro. Sugiura Yasuyoshi.

Japanese pottery continues to thrive and move forward, while cherishing past traditions.

It's an exciting time indeed.

In Clay, A Flower Blooms (Part Two)

In Search of One's Self Through Clay

Click here for part one

Click here for some photos of his work

W: How did you first meet clay? W: How did you first meet clay?

S: Well, it's not like I was particularly creative when I was small; I didn't like to draw, and I wasn't the studious type. When I reached the senior year of high school, I was confused as to what to do. I didn't want to work, so I figured that going to college would allow me 4 more years of fun. I then looked through a college magazine, and there it was: Geidai. I thought art school would be fun, so I applied (Wahei's note: I don't want to beat anyone over the head with this, but Tokyo Geidai is very likely the most difficult university to get into in Japan). I wasn't accepted on my first try, but I was accepted on my second attempt. Coincidentally, during exam preparations, I happened to walk into a Bizen exhibition in Tokyo. Yakimono might be nice, I thought.

Even before matriculating, I asked my professors at Geidai to send me to kiln sites so that I could learn pottery firsthand. For a month before school, I studied in Kasama, as well as in Fukuoka under Kozuru Gen (acclaimed Kyushu potter who now lives in the US). At Kozuru-san's kiln, all I did was cut wood, fire kilns, and then cut more wood. I thought that was what yakimono was all about.

But when I actually began studying at Geidai, I was surprised to find that hey, there's such a thing as a gas and electric kiln, and various kinds of clay. Everything was so simple. There were a lot of elite kids at the school, and together, we tickled our egos as we potted. But as we potted, I started to wonder if this was all that pottery was supposed to mean. What is a kid like me, who could hardly study, doing here with all these talented kids, I thought. Everyone is so perfectly content with making functional vessels on a potter's wheel. But on an electrically-powered wheel, you can basically make something by closing your eyes and keeping your hand still. To put it crudely, you could lose yourself within a potter's wheel. That scared me.

Right when I was having these doubts, a professor of mine came up to me and said, "Sugiura, ceramics is essentially stone." He proceeded to break a piece of stoneware in half, and behold, the inside of the yakimono did indeed look like a rock torn in two. Curious, I make a clay stone and fired it. I was happy to find that I too could make a stone. That sensation was so vivid, so fresh, and it gave me a sense of happiness I couldn't get through making a vessel. Vessels have a purpose. Small rocks don't. Such a notion was oddly satisfying. At the time, Yagi Kazuo's objet d'art works were all the rage. I tried copying his works, but my copies were far too immature and crude, since my emotions were just pouring from the clay. Hmm, objet d'art isn't me either, I thought. I tried making more small ceramic stones, and I started painting them, glazing them, making symbols on them, etc. But after I fired them, I looked at the end products and thought, "how boring." They were fun whilst making them, but as works of ceramics, they reeked of human ego. But if the stones were silent, I felt something special could be found inside of them.

Do you remember in high school, when the principal gets up to make a speech in front of the whole school in a large auditorium or gym? All the kids are lined up in neat little rows, while the principal thinks he's big and authoritative from the safety of his elevated podium. All of us look up and focus on the principal, all eyes are glued on him, as he's the only guy talking straight at us. But to the principal's point of view, we might as well be potatoes, or a bunch of small pebbles on a river shore.

But even those tiny pebbles, if you bother to pick one up, can turn into a recognized, identifiable thing, as something both individual and unique. I wanted the same ideas in my ceramic stones. I wanted to make a bunch of these clay rocks, while instilling each rock with life energy. If all these rocks are gathered in a single place, the accretion of all that energy within each single rock would turn into something completely different, something powerful, something greater than the strength of a single ceramic stone. I went ahead and made 100 stones, fired them, and went straight to exhibition with the works, and I won a prize. In the local paper was written, "Young potter Sugiura Yasuyoshi makes a splash, an interesting new kid on the block, let's look forward to his next work." Of course I'm really happy with winning. Then, I thought that if I could get a prize with a hundred stones, I thought I could get the Grand Prix with 10,000 stones. I got straight to work, and quite predictably, that work didn't even make the exhibition list (chuckling to himself).

W: Well, I guess quantity wasn't the point, huh.

S: I got over it right away. I thought to myself, then and there, that I shouldn't be swayed by awards that critics dish out. But I did realize at that point in time that the small size of my works could be a conceptual limitation. That's why my works gradually grew in size, and stones turned to boulders. A boulder is essentially a mountainous landscape. When mountains crumble, boulders are formed. In each boulder lies the innate power of mountains. I thought that if I could trap the energy of mountainous boulders into each ceramic stone, then make a group of those stones and put them together, I could capture and build a single and unique, energetic, intangible force. You see, like the human race, no two stones look alike. But here came the critics, praising my works because, "Sugiura has put identical objects in meaningful groupings." It's not so simple.

|

Work by Sugiura Yasuyoshi

from "Ash-Covered Ceramic Stones" series

Photo by Hatayama Takashi

Sugiura Yasuyoshi's yard

Japan, historically, had always a culture of copying. Even in the art of flower arrangement or in the Way of Tea, one copies the traits of the outside natural world and transposes such traits into one's own movements, so that the "truth" behind a thing in nature is captured within one's self. It's exactly the same with primitive magic. Since the human being was, essentially, a very weak creature, men tried to copy nature's characteristics, in order to wield and capture the power of the spirits of nature. Likewise, I've always tried to take the energy found within nature and build it up within myself. And with that energy, I tried to inject it within each stone, boulder, and flower I made, without trying to disrupt that energy with gaudy decorations or coy games. When all that energy is gathered and put together in groups, I thought a new, powerful landscape could be formed. I try to capture the spaces within nature, and this always requires a free, unfettered spirit.

W: I know you revere clay, perhaps even more than your contemporaries. But through that reverence, don't you think you are already fettering yourself from free-forming creativity? In other words, is not the material your greatest restriction in itself?

S: I use clay because I like it. I know other people might use certain materials out of sheer convenience. But not me. The only reason I make things is because I want to use clay, and clay alone. Restrictions and limitations will never disappear. Besides, "making something" is a restriction in itself. Some can say that in ceramics, the fact that you have to "fire" a work, or the fact that you "glaze" a work, are further restrictions. But not me. To me, those processes are what make working in clay so enjoyable. The joy is received through using a singular material, and finding how to make it taste good, just like cooking. Of course, this has become a discussion on material theory. Perhaps Kaneko-san might say something very different than what I just said.

W: Err, actually, I had wanted to tell you earlier, but your interview is going to appear back to back with an interview with Kaneko-san. You're being paired up, Sugiura-san.

S: Well, isn't that interesting! (laugher ensues) Actually, at my last Nihonbashi Mitsukoshi exhibition, Kaneko-san came to see my works with Karasawa Masahiro (also of MOMA Tokyo). But I was drinking tea and chatting with a customer at the time, so I hadn't the opportunity to talk to him directly. Really, there are many, many things I would like to ask and talk to him about.

|

|

|

|

|

Sugiura's ceramic Angel's Trumpet (top) is deceptively realistic; his himawari (above) has platinum-painted seeds that look good enough to eat.

PHOTOS COURTESY OF NIHONBASHI MITSUKOSHI

|

|

|

|

|

Ideologies of a Potter

W: Does it ever make you happy to think that your work, like much of the art in the world, will remain, long after you've physically passed from this world?

S: Maybe it's because I make works that I can say this, but a work is like one's own child: from the moment of its conception, it takes on a life of its own. So at least in my mind, an artist does not dwell upon the works he's made. To put it rather crudely, my work is like bodily excrement. And besides, if one can't possibly know what it is like after death, how can I possibly know or care for how my work will be interpreted after I die? For me, there's no point in dwelling on something I'll never understand. I just know that I want to create things, right here, right now. And when it is conceived, such is the end. Then, I start anew. It's within this perpetual cycle that I find myself ending my life with.

W: Wow (I was left chewing on his words for a few moments in time, as I looked blankly into a sun-filled corner within Sugiura-san's home).

S: Collectors come up to me and say, "Well, isn't it nice to be an artist. Your works will remain long after you die." But I see it differently. Once he stops playing, a musician's music ends at that very moment. The sound begins to fade, once he puts down his strings. In the hearts of the audience, that beautiful, eternal sound might always remain. It might even remain through recordings. But to that musician, after a song is played, that beautiful, aesthetic experience of being touched by one's own music stops the moment he stops playing. And he will never experience that same feeling he received at that very moment, ever again. It won't be the same. Because the musician can't experience the same feeling, he picks up his strings and plays again. He tries to make something new, to experience a new and different feeling. The body wants, so he plays again.

W: That's beautiful. What a thought.

S: When I look at some of my own works, I sometimes think, "Well, that's nice." But it isn't a feeling of being overwhelmed by beauty. It is the feeling of being overwhelmed by nostalgia. I remember when Kamoda Shoji jumped into the forefront of the art scene when I was a student. He was able to achieve a new expressive quality in clay, an expression that had never been seen before. When I first saw his works, I was just overwhelmed with emotion. It's been 30 years since that day, and I see Kamoda-san's works from time to time. But they have all faded in my mind.

W: For me, I'm always overwhelmed whenever I see his work ((Wahei's note: Kamoda is one of my all-time favorite potters, hands down. He is a potter I will promise to cover in the future.).

S: When Kamoda-san first appeared during my college days, I really thought, "amazing." He was my idol; just look at those textures he could bring out in clay, those original and unique designs. I'm talking about the works he made right before he became famous. Those were his best works. He was ripe, capturing all the energy around him. Just ready to explode with artistic creativity.

W: If I comprehend what you've just been telling me, it seems as if you're saying that you can never beat that first love, that first moment you interact with and meet a work of art. But on the other hand, it's long been said that works of great beauty stand the tests of time, and in other words, are universal and will not change.

S: When you go to a museum and see a great work of art, and then you see it two or three more times later, I just don't think you can surpass that fleeting and special moment when you first laid eyes upon it. This notion might be different for artists; it might be different for each viewer. But what I try to achieve in my own work is that very special, initial moment of meeting something or someone for the first time.

W: I remember talking to Uraguchi Masayuki (Sugiura's underclassman at the Geidai) about a similar thing. The difference between other art forms and pottery, he said, was that in pottery, the potter can only make half of the work. The other half, you leave it up to serendipity, fate, and that special, first meeting between one's self and one's work after one finally pulls it from the kiln.

S: I think what Uraguchi-kun was trying to say was this. Actually, a potter can very well predict how his kiln works inside. In a potter's mind, lies a visual image of the "best outcome" that could be achieved. For a painter, his art is completed once he puts down his brush. But for those who make pottery, we're not just letting the kiln gods determine our works. It's not simple chance. We know how to load the kiln, how to fire the kiln, and where to position each work. But the difference is that we can't see what happens within the kiln -- we can't physically be present to apply the finishing touches with our own hands. But when we open that kiln, we can finally meet our work for the first time, and can see if the work actually fit the image in our heads, if it was worse than that image, or if it was greater than our wildest expectations. It's that raw and pure emotion -- the happiness one receives when he meets his work for the first time from the depths of a kiln. That's what makes pottery so special. But when he actually experiences that special feeling, the feeling has already ended. It is but the past. So, he picks up clay once more and starts anew. And for a true potter, there is no set path that one must take. He will not dwell on making the same things as before. He will strive for new forms of expression. He may always try to reach the same mountaintop. But the true potter will forever pursue a different path than the road he'd already taken.

End interview with Sugiura Yasuyoshi (1949 - )

Interview & translation by Aoyama Wahei

for www.yakimono.net and www.e-yakimono.net

Have a wonderful weekend.

See you next week.

All photos on this page by Aoyama Wahei unless stated otherwise

PHOTO TOUR OF WORK BY

SUGIURA YASUYOSHI

See part one for more photos

Below Photos by Robert Yellin

From the 2004 Mitsukoshi Exhibition

INDEX TO

ALL STORIES

by Aoyama Wahei

|