|

Kyoto -- To Travel the Past, In Search of the New

Chapter One: The Birth of Sodeisha

(Click here to view chapter two)

Welcome back. From the very beginning, a short caveat. This column has no major constrictions, other than that my censor is Robert-san, and that my focus is on Japanese pottery.

Hence, there will be weeks when I focus on individual potters. Other weeks, I will focus on pairs or groups of potters as a movement. Sometimes, I will simply focus on a concept of pottery, or a type of ware or technique. Other times, I will unleash unsympathetic vengeance on the pundits who have confused us all. Or on the politics within the Japanese ceramic world. Or of the great stories in pottery history and legend. Einin Tsubo, anyone? And other times, I will do none of the above and just ramble on about why I like a particular pot. Furthermore, certain subjects will be separated into two or three segments, as the subject matter is such that I can not do justice in a brief one-week essay.

And now, after bouts of doubt and trepidation, I bring to you the first full installment of Japanese Ceramics Now.

Takiguchi Kazuo (1953- ) and Akiyama Yo (1953- ), I believe, are two of the most exciting Kyoto potters in Japanese ceramics today. They are emblematic of a storied tradition in Kyoto -- the idea of Onko-Chishin (温故知新).

Loosely translated, this concept means "to travel the past, in search of the future." In other words, one must understand the traditional in order to give birth to the new.

The common perception is that Kyoto is a conservative city, in that not only is Kyoto the heart and soul of Japanese traditional culture, it is also the noble vanguard of our ancient traditions.

This perception is slightly skewed.

All traditions start out as mere fads or trends. After a prolonged tendency of applying the trend over many years, the fad no longer remains a fad. It becomes like the air we breath -- so basic, so effortless, so engrained into our psyches. The fad, therefore, has turned traditional. This is a natural progression.

In other words, all traditions were once contemporary.

Thus if Kyoto is the birthplace of Japanese tradition, it must also stand that Kyoto is a trendsetter, forever on the cutting edge of Japanese aesthetics. It truly is. Kyoto has always opened its doors for the new, while continuing to embrace, cherish and protect the old.

There you have it. Onko-Chishin.

In such an environment, legendary artists such as Rikyu (yes, I consider him an artist), Chojiro, Koetsu, Korin, Ninsei, Kenzan, Tomimoto Kenkichi, Kawai Kanjiro, Ishiguro Munemaro, Kusube Yaichi, and eventually Yagi Kazuo, were bred (a mind boggling list, isn't it). These artists were not reactionary, but revolutionary in the techniques, methods, and concepts used and created.

Takiguchi and Akiyama fit this fine Kyoto tradition. Yet, before I delve into a deeper discussion on these two potters, I believe it is not only helpful but essential to introduce to a wider audience the ceramic art scene in Kyoto in the 20th century. Only then can we begin to understand the aesthetics of Takiguchi and Akiyama.

A group of ceramists emerged in the 1920s and 30s who rocked the Kyoto scene. They are considered the first wave of "individualist" potters in contemporary Japanese history. They, in a sense, dominated Kyoto ceramics for a good half-century. An interesting fact: many of these potters lived on the same cross-section of Kyoto, called Gojo-zaka.

Two of the giants were the Nitten (Japan Fine Arts Exhibition) potters Kusube Yaichi and Kiyomizu Rokubei VI. Together, they helped promote Kyoto pottery, while passionately nurturing the birth of bright, young potters.

Kusube Yaichi (1897- 1984), dubbed by some as "the modern-day Ninsei," gained fame for the technique of elegantly layering different colored clays, while applying intricate overglaze enamels over the clay body. This technique eventually awarded him a Fellowship into the ultra-exclusive Japan Art Academy. Only 10 potters were ever named Fellows, while 31 men (yes, all men) were graced with Living National Treasure status. Some famous Fellow names are:

Itaya Hazan (the first full-fledged modern artist/potter in Japanese ceramics), Tomimoto Kenkichi (the only man to be both a Fellow and a LNT), Hagi's Yoshiga Taibi, Kutani's Asakura Isokichi, and Kyoto's Kiyomizu Rokubei the 6th (1901- 1980).

Kusube was a bitter and jealous rival of Rokubei, who was the head of a dynasty of famed Kyo-yaki potters (and was inducted as a Fellow himself). Rokubei was known for his poetic painting skills (he had studied Japanese brush painting), and was an aggressive developer of various glazes. The two were so antagonistic, in both art and in personality, that when a journalist went over to one's house, it was forewarned that the other's name must never be mentioned. Such was the tense artistic air in Kyoto in the 1930s to the 1950s.

Kiyomizu Rokubei lived in Gojo-zaka, right next door to another bright, individualistic potter by the name of Yagi Isso. Yagi, in turn, lived next door to the brilliant Kawai Kanjiro (1890- 1966). Imagine what sort of neighborhood that would have been!

I like to imagine the scene in Kyoto as something akin to Paris in the late to mid 19th century (van Gogh and Gauguin), or the Greenwich Village in Manhattan in the 1950s (Pollock, Lee, de Kooning). When there exist special enclaves in a city where artists can congregate, to discuss and debate love, life, art and politics, great art scenes are born. The energy is vast, the dreams, boundless.

It was in such a scene that Yagi Isso's and Kusube Yaichi's aesthetic ideals united, and they got together to form an influential pottery group called Sekido (Red Clay). Their inaugural proclamation was as follows:

"The men of red earth will study and pursue the depths of natural beauty, in search of a beauty in ceramic art that is eternal and will never perish, and to be able to express that beauty with the abilities given to them by a mystic light, and who were born into this world to create."

I like this proclamation.

The artists of Sekido were striving for a ceramic aesthetic that was not restricted by conventions, and to seek individuality through freedom in expression.

Sound familiar to anyone?

Well, Yagi Isso had a son.

His name was Kazuo.

If I had to name just one potter who brought about a sea change in how we perceive ceramics in the 20th century, and whose legacy vividly lives on today, without doubt I would choose Yagi Kazuo (1918-1979).

Yagi founded in 1948 the legendary avant-garde ceramic art group Sodeisha, or in English, "The Society of Running Mud."

With Yagi as its leader, the art group had such core members as Suzuki Osamu, Yamada Hikaru, Kumakura Junkichi, and satellite member Tsuji Shindo. Highly artistic, individualistic potters -- all were intellectuals, yet without pretensions of academia.

They took the proclamation of the Sekidosha and expanded it as their own.

The Sodeisha were extremely important in that it was the first group to openly contest the concept of functionality within ceramic art. As contemplative but witty Suzuki Osamu put it, "Every day, we fought valiantly to discover new ways in which we could close that gaping hole on top of a tsubo (jar)." (This theme will be brought up in Segment Two, when I fully discuss Akiyama and Takiguchi).

In effect (yet not necessarily in intent), the Sodeisha tore down the walls between fine art and craft art. This was not the Sodeisha's concern, however. Yagi, until his death, always referred to himself as a "chawanya" (a teabowl craftsman). In other words, one can view this as an expression of Yagi never considering his sculptural pottery to be on a higher or different plane than a chawan, or that there were distinctions between craft art and high art, especially in the context of Japanese culture and traditions. The craft of the lacquer and wood craftsman, sword smiths and potters, dye artists and kimono weavers, were all "art," and could not be fragmented or divided into an overly simplistic bifurcation such as between fine and craft art.

In many ways, the Sodeisha were more than just a movement advocating a certain aesthetic, or promoting objet d'art over functional wares. They were a highly philosophical group that valiantly confronted the concept of form in an era where functionality in pottery was its prime raison d'etre, and they sincerely tried to overcome that hole atop a jar. If they could close it, victory was theirs.

"Stop promoting Yagi and the Sodeisha. We were doing what they've been doing a year before the Sodeisha!"

So said Uno Sango (1902-1988) to an art journalist in the 1950s, obviously fed up with the enormous attention the media was giving Yagi's group, and not his. The "we" in the above quote refers to Uno's avant-garde group Shikokai (Society of Four Harvests), consisting also of Hayashi Yasuo, Shimizu Uichi (a future LNT) and Kimura Morikazu (although the two parted ways with the Shikokai within a year). Uno had strong pride in the fact that Yagi wasn't actually the first potter to eschew form for abstract expression in clay.

The Shikokai were an interesting, albeit oft forgotten group, overshadowed by the astounding charisma of the members of Sodeisha.

Yet, why was the spotlight not focused on the Shikokai? Uno made some memorable work, such as vases in the shape of dogu (ancient clay figures from Japan's Jomon Period).

A fundamental difference between the Shikokai and the Sodeisha was how each group perceived the medium of clay.

For the Shikokai, clay was only a means to an end. What they tried to achieve in pottery was the elevation of ceramic art into a Western conception of fine art, or akin to sculpture in the line of Rodin or Brancusi.

As previously mentioned, Yagi thought nothing of trying to elevate art to a higher art form. Rather, he was perfectly content to think of pottery as craft (although in Yagi's head, craft was no different from fine art). Thus in other words, the Japanese perception of art was such that craft was already in extremely high regard, and that the craftsman and the artist were analogous.

Yagi's central preoccupation was clay. Clay as a material, and the variations in expressions that could evolve from the fundamental characteristics of clay, were elements that Yagi cherished and tried to express. He was a potter, and he could not extend himself otherwise. To Yagi, clay was everything. This reverence propelled his works to a higher plane.

In other words, the potter without clay is nothing. Pottery begins and ends in clay. It is not a means, but the end itself.

And what is clay?

This question, proposed and battled on by Yagi Kazuo and the Sodeisha, and which could be seen from the early 1920s in the likes of Kusube and Yagi's father Isso, lives on in the works of Takiguchi Kazuo and Akiyama Yo.

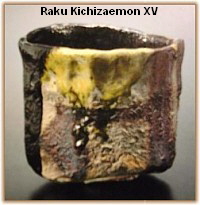

Kyoto is again bursting with creative artists of the same generation as Akiyama and Takiguchi. Some are a few years older, like the likes of Yagi Akira (the son of Yagi Kazuo) or Kiyomizu Rokubei VIII (the grandson of Kiyomizu Rokubei 6th ), while some are a few years younger, such as Raku Kichizaemon XV (the heir to the Raku throne) and Fukami Sueharu (the greatest Seihakuji potter working today).

Above: Yaki Akira

Yet, even with so many star-studded names, I do not hesitate in focusing on Takiguchi and Akiyama. Why?

For one reason, the two artists stand out in their perilous quest to understand the nature of clay.

They were born in the same year, and went to the same university.

Their teachers?

- Akiyama Yo -- Taught by Yagi Kazuo

- Takiguchi Kazuo -- Taught by Kiyomizu Rokubei VI

We are all entwined.

See you next column, when I will introduce to you the aesthetics of Kyoto Ceramics Now, from the eyes of Akiyama and Takiguchi. You'll be surprised.

by Aoyama Wahei

(I highly recommend Louise Court's book on Isamu Noguchi as essential reading in grasping Yagi Kazuo, although I have failed to refer to her wisdom when writing this particular article.)

|