|

Kyoto -- To Travel the Past, In Search of the New

Chapter Two: Takiguchi Kazuo and Akiyama Yo

(Click here to view chapter one)

Ideas and Pottery.

I mentioned in my first column that both are graced with perpetuity. Long after we've turned to dust and bones, they'll remain.

I further mentioned in my second column that the pottery scene in Kyoto, along with virtually all of its artistic traditions, is representative of the concept Onko-Chishin, meaning to "travel the past, in search of the new."

Today, I introduce two Kyoto ceramists that combine both ideas and pottery into a singular entity, a synthesis of what makes great art.

What lies within their pots are concepts.

|

Above: Takiguchi Kazuo

Above: Akiyama Yo

|

|

For Takiguchi Kazuo (1953- ), it is the power of language, or the lack of it: into silence we fall, but it is this silence that allows for harmony between us and our surroundings.

For Akiyama Yo (1953- ), it is the tumultuous relationship between life and death, the hidden tensions between interiors and exteriors, of prosperity and decadence.

Born the same year and studying at the same university in Kyoto underneath the same teacher, it may seem that they have more than fate that entwines them.

Some facts are in calling.

Akiyama's heritage is not from Kyoto, or even near it. He was born in the western land of Yamaguchi Prefecture, a prefecture famous for its Hagi wares.

On the other hand, Takiguchi was born in the heart of Kyoto pottery, Gojozaka. He grew up being neighbors to such names as Kawai Kanjiro, Kiyomizu Rokubei 6th, Yagi Kazuo, Kondo Yuzo and Fujihira Shin.

Their paths first crossed when they entered the Kyoto City University of Fine Arts. For those unfamiliar with the Japanese art school system, the Kyoto Geidai (its colloquial name) is oft considered the most difficult university to be accepted to in Japan, even more difficult than Tokyo University. The young Akiyama flourished underneath the tutelage at the elite school. And at the same time, he breathed in the air of Kyoto, a scene filled with art, ideas and tradition. The studious, serious Akiyama went on to graduate studies, and graduated from the Geidai with an MA in Ceramics. The year was 1978.

Takiguchi, on the other hand, couldn't keep up with his studies in Contemporary Economics at Doshisha University. Confused, he tried his hand at pottery by apprenticing briefly with Kiyomizu Rokubei 6th, the great Nitten potter who lived next door. Yet Takiguchi eventually felt he needed to go to art school, and was accepted to the Geidai. Takiguchi floundered for a bit, and eventually dropped out to become a truck driver for dried noodles. The year was, again, 1978.

In the year 1979, the man who taught both of them passed away. In the year 1979, the man who taught both of them passed away.

His name was Yagi Kazuo.

Indeed, their lives verge like star-crossed lovers. But to categorize them too closely is to oversimplify.

I will claim that they both are, essentially, Kyoto potters.

Yamaguchi-born Akiyama is an outsider, but has fully assimilated himself into the landscape. His "second hometown" is now his permanent home.

Furthermore, he took up an offer to teach at his alma mater (following the footsteps of his mentor Yagi), and Kyoto Prefecture awarded him a Cultural Prize in 1994, basically crowning him as one of "their own."

Kyoto-born Takiguchi migrated his workshop next to Lake Biwa (the largest lake in Japan) in Shiga Prefecture, although his abode remains in Gojozaka. Thus physically, he is no longer a Kyoto potter per se. Nonetheless, he was awarded a Cultural Prize from Kyoto Prefecture in 1996. In a sense, it may be that "once a Kyoto potter, forever a Kyoto potter." (The same holds true for Kako Katsumi, who was born and raised as a Kyoto potter, yet eventually moved his workshop to Hyogo Prefecture.)

The physical similarities seemingly stop there.

I've searched, but I can't seem to find a common relationship between the two potters. Perhaps it would be easier to just call and ask, but then again, it might be quite rude to ask, "So, are you and Takiguchi chummy?" when they actually loathe the other. In other words, I've dug for clues, but haven't found an answer. They've never exhibited together, although their works were once shown side by side in a 1990 Takashimaya exhibition. They both exhibit often at Gallery Maronie in Kyoto, but never as a group. In other words, they lived in the same city and are representative of the city's ceramic scene, went to the same university at the same time, were both studying pottery and were taught by the same teacher, but I've never once heard them speak the other's name, or see them grouped together (although Honoho Geijutsu ran a special a while back on Takiguchi, Akiyama, Fujimoto Yoshimichi, Takauchi Shugo and Matsui Kosei).

Of course, there are no Sodeisha movements or pottery groups like in the days of old. But I've also felt that Kyoto potters are usually a closely knit bunch, and the lack of connection is somewhat puzzling. In any case, I digress, for what is important is not the artist or their relationships, but the art.

What is clay?

This question perplexed Yagi Kazuo, and was one of the driving elements in his pursuit of understanding ceramics.

This pursuit lives on in his students Takiguchi and Akiyama.

The majority of Akiyama's works are massive installation pieces: some stretch for over 18 meters. His larger pieces consist of separate building-bloc-like pieces that are put together to form a whole. Some works hang from ceilings, other works take up the entirety of a gallery space. But in all his pieces are the common characteristics of (1) the color scheme black, and (2) cracks. (For a photo tour of Akiyama's work, click here.)

It seems as if Akiyama sees in clay a multitude of possibilities -- the possibilities in the life energy of Eros, and its antithesis, the death energy of Thanatos. Take for example the series of works entitled Oscillation. Rippled cracks swim throughout the entirety of the surfaces, cracks placed intentionally by Akiyama through the use of a hand-held blowtorch/gas burner (he later fires pieces in a kiln by reduction, thereby achieving the black, rustic veneer). And what are cracks? Cracks are actually an exterior expression of what's going on underneath surfaces. They reveal what takes place inside. Akiyama is trying to express an energy that lies hidden within clay: a visceral, vibrating energy that are metaphors for life. Thus, what lies within clay is Akiyama's primary preoccupation. What is the material? Why use it? What can it express? What are its characteristics? Cracks are a cry to be heard from underground, a leitmotif for the innate energies that exist in not only clay but in us, our surroundings, and of nature and natural-occurring events, like the sheer might and terror of earthquakes.

Above and Below:

Work by Akiyama Yo

Above and Below:

Work by Akiyama Yo

In a sense, all of the above revolve around a certain planet: Earth. Clay is Earth, and with it, Akiyama can express the eternal.

"I was peeling a tangerine, and as I was peeling I thought to myself, wouldn't it be interesting if I could peel the skins off of clay?"

He took a lump of Shigaraki clay, and began to slightly cook the exterior. Akiyama put his burner down, and with his bare hands, began to slowly peel off the top layer of clay.

This technique further sparked his creativity. He began to torch clay that he had formed into cylindrical shapes, and began peeling them apart. Akiyama then laid these on the ground, and he had a new line of work, the "Peneplain Series." They were linear works that gleaned with a seductive, contemplative nature that was, quite curiously, oddly Japanese. Akiyama's newer line of works, fired in a kiln and given a rusty texture, is essentially the "sabi" from Rikyu's wabi-sabi philosophy. The kiln allows Akiyama to fully capture the Kokuto (black ceramic art) aesthetic that his mentor Yagi excelled at.

Akiyama can be considered even stoic in his pursuit of the image within his head, meticulously burning, carving, and shaping the clay to the most exact of details, then tearing them apart (again calculated), shaping and texturing the clay again, and then putting the pieces together.

"You see, there are two elements to my work -- construction and deconstruction. I shape clay into a certain form, torch it, then tear it apart. It's a process of life and death, creation and destruction. And in this process, I try to understand how, through my techniques, I can embrace clay for what it is, and how it wishes to be expressed."

Akiyama listens to clay with the most sincere of hearts, perhaps more than any other potter working today.

Yet there is another potter who listens to clay, and sometimes, all he can hear is silence. For when there are no words to express something, how can you know it's even there?

"The limits of my language are the limits of my world. And in that respect, whatever I say must limit the world and make it finite. All I know is what I have words for." - Ludwig Wittgenstein.

Takiguchi experienced the truth behind the German philosopher's quote during his time in England.

He realized, then and there in London surrounded by English, that for all his life, he had only used Japanese. He ate, drank, talked, walked, slept, and dreamt in Japanese. He even potted in Japanese. Even before he potted a chawan (teabowl), he had to know what a chawan was. The word came before his art. This frightened Takiguchi, for he thought that the breadth of his creativity as a potter was limited by language. What are words? What do they mean to me? What do they make me? And what is clay? This internal struggle was more than a matter of simple semantics.

His answer came from two types of pottery.

One side of Takiguchi learned to embrace, rather than eschew, language. In language are stories to be told, feelings to be expressed, and art to be made. Hence, by always first contemplating what a particular word meant, he then proceeded to "materialize" the word into clay through the technique of hand-pinching. Takiguchi began to name all his works. Akogarete itanoni is literally "I used to worship." The work is a tiny red motorcycle. More tiny figures started popping out from Takiguchi, recently from words taken out of a Japanese ancient book of poetry called Tsurezuregusa. He took the poems within, and made a small figure for each section to symbolize the words on the page (although he changes the poems around to fit a modern aesthetic). When a caption referring to sake appears, he makes a guinomi (sake cup). A section that reads "put the palms together from the heart, and in your hands will spring flowers" turns into a clay figure of hands together in prayer, decorated with a flower motif. And at another exhibition, he made all his chawans using various single letter Kanji. For example, his work Yu, or Sunset, is a Raku teabowl colored in a beautiful limbo between an autumn orange and salmon pink. Thus in this embracing of language, Takiguchi the potter showed a tremendous range in what he can create, from clay dolls to chawan and other functional wares. This range, then, is simply an indication of the range of words themselves.

Takiguchi instills in his works what one would call a tongue-in-cheek, mirthful and witty aesthetic. Some can draw parallels to this side of Takiguchi with Kyoto elder Fujihira Shin and his unique, poetic world. But like Fujihira, I believe that both of these artists' best works are actually not their playful, figural ones.

|

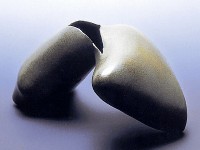

Above and Below:

Work by Takiguchi Kazuo

Above and Below:

Work by Takiguchi Kazuo

|

Takiguchi has another side to his persona.

And it is drenched in the roar of silence.

Using the tatara technique of using boards and pulleys to lift, wrap, and shape clay, he makes organic, cloud-like black sculptures that baffle but captivate. The forms are sleek but puffy, smooth but jagged. In these contradictions of qualities, one can see that Takiguchi has reached a point of expression wherein he could not think of words to express an emotion, or that which lies around and before him, in both past and present. Rather, Takiguchi found that when stripped of words, all that was left was nothing but empty silence. Hence, he doesn't even title the works. They are left by the galleries as "Untitled" (but that in itself is a title, which is rather unfortunate when thinking that Takiguchi was trying to reject labels, titles, and cognitive thought). They are works to express the subconscious state of nothingness, or 無 (Mu). I can see parallels to Zen in this concept from Takiguchi's works.

And as Robert Yellin wrote in a Japan Times article in 2001: "Takiguchi's rounded forms all have some sharp, jagged opening that pulls the viewer into the piece, so much so that one wants to look inside that black hole full of mystery. It's the empty space that actually gives the piece its shape. Seemingly insignificant at first, it's very much the dictator of form."

Indeed, it is the hole that makes the piece, and signifies the emptiness left behind when words run dry. Why use clay to express this loss of language? Takiguchi, in his own words, explains:

"Clay is Earth, and it is just as natural as air. It transcends the concept of a mere medium. And by interacting with something like Earth, I find that I can find new ways of looking at and understanding the world around me."

Takiguchi and Akiyama are representative of a fine Kyoto tradition of pushing the envelope and expanding tradition, rather than simply accommodating it. I enjoy their works, not only because they look good, but because within their clay lies a solemn spirituality that inspires and resonates. They are also further emblematic of the Kyoto tradition of (1) not using a potter's wheel, a methodology popularized by the chawan potters Raku Chojiro and Honami Koetsu, and (2) using Shigaraki clay, as Kyoto never really had an indigenous and characteristic form of clay.

One should not underestimate the influence of these two ideas, as I believe they are major reasons why Kyoto pottery contains an eager liberalism. By resorting to such techniques as hand-pinching, gas burners and tatara, the potter is free to express himself in more ways than a wheel could allow. This gives birth to more freedom in forms. And the fact that Kyoto did not have clay like that of Bizen or Shigaraki meant that Kyoto as a pottery center did not have to dwell on wood-firing. One can get too entrenched in the concept of Japanese wood-firing as a tradition, that it can suffocate freedom to explore other methods (Kaneshige Sozan was publicly bashed when he first devised a way to get great Bizen hidasuki (fire chords) from an electric kiln). The Kyoto potters had more leeway to explore new techniques in glazing, firing, and forming because they did not have a particular pottery tradition to adhere to. Hence, this liberalism gave birth to progressive pottery, seen in the likes of not only Yagi, Takiguchi and Akiyama, but such potters as Ninsei and Kenzan, even Tomimoto Kenkichi, Kawai Kanjiro and Ishiguro Munemaro.

I regret the fact that I can only generalize and capture but fragments of the two potters' aesthetics in this weekly column. But I think it is fair to say that Takiguchi and Akiyama are not just any ordinary avant-garde or "contemporary" potter.

In their art lies the idea that the material they use can help them grasp the world around them.

To both Takiguchi and Akiyama, Clay equals Earth.

And what can be so basic, so simple, and ever so natural?

On that note, see you next week.

by Aoyama Wahei

EXTRA:

At Geidai, Yagi asked Takiguchi:

"Why the heck have you not been showing up for class?"

Takiguchi replied: "I've been driving trucks to make a living."

Yagi shakes his head and says: "Well, do as you must, but if you ever pot, please show me what you've got."

Takiguchi took the advice, while at the same time dropping out of school. When he had time to spare from driving his truck, Takiguchi would pot, and then bring the pots over to Yagi (Takiguchi actually knew Yagi when he was growing up in Gojozaka, but didn't know Yagi was a potter until college. He just referred to Yagi as "that old man Yagi down the block").

One day, he brought a piece to show Yagi, shortly before the latter's death. Yagi says: "Wow, this is prize material! You have to enter this, Takiguchi."

Takiguchi shrugs his shoulders, wraps it up, and enters it in an exhibition. He wins. Hence, the truck driver blossomed into a full-time potter.

Thank you, Yagi-sensei.

|