|

Yellin's gallery

sells pieces from

the kilns of Japan's

finest potters

Photos on this

page are courtesy

of the Matsubayashi

family and the book

"The Asahi Pottery

in Uji" by Korinsha.

|

|

Tradition As Air and Spirit

The Matsubayashi Family

and 15 Generations of Asahi Pottery

Story by Aoyama Wahei

for The Studio Potter, Volume 32, Number 2

Yukoan playing with grandchildren

"Tradition is simply natural. It's always been there, and has always been with my family. It is like the air we breathe." So speaks Matsubayashi Hosai XV with a sincerity I think is heartfelt. In his words rest the storied weight of four centuries. Hosai XV not only inherits but embodies the lineal tradition of Asahi Pottery, a type of ceramic ware made exclusively with clay from the Uji region of Kyoto, Japan. From father to son, from son to grandson, the Matsubayashi family has passed on the traditional techniques of Asahi for fifteen generations since the Momoyama Period (1573-1615).

Lineal traditions in Japan, seen by one unaccustomed to such customs, can appear excruciating, even suffocating. It is like a perpetual entrapment, a shackled role that one is born into, a responsibility that one has no choice but to live.

Even so, Hosai speaks of tradition as oxygen, as something that is always there but can't be felt, as something that is essential to life but is not given further thought. Tradition is not a bane, but is the backbone of Hosai's existence. Tradition, to Hosai's family, is life itself.

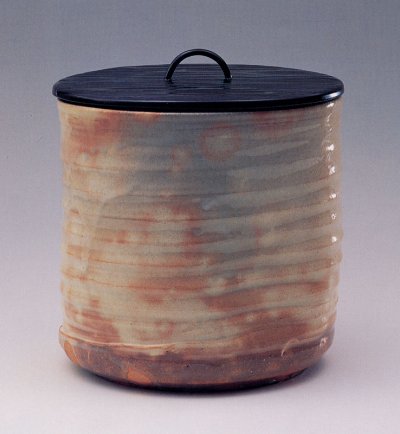

Hanshi Kohiki Mizusashi by Yukoan

In Japan, lineal traditions abound. Kabuki actors, martial arts, sword-makers and kimono-weavers- all are professions in which fathers pass on traditional techniques to their sons. It is not an understatement to claim that the Japanese culture of old has survived by the bestowing of traditional techniques through family legacies. It has been this way for centuries.

The same can be said for yakimono (pottery). The Kaneshige family of Bizen fame, the Nakazato family in Karatsu, the Miwa family in Hagi, the Raku chawan tradition continued by Raku Kichizaemon XV -- great are these families' contributions to preserving and imparting artistic legacies for future generations through the aegis of lineal traditions.

Like the aforementioned families, the Matsubayashi clan is the founder and protector of Asahi, a type of stoneware predominantly associated with the Way of Tea. Kobori Enshu (1579? - 1647), one of the great Tea Masters succeeding Sen Rikyu (1522 - 1591) and Furuta Oribe (1544 - 1615), was a major patron of the Asahi kiln, calling Asahi one of his "Seven Kilns." With Enshu's support and supervision in the 1640's, the Matsubayashi family established itself as an important "chawan-ya," or a family of tea bowl / tea ware makers. Enduring vicissitudes of prosperity and wane, the present Asahi kiln flourished through the endeavors of Hosai's father Yukoan (Hosai XIV). His extensive research into the workings of kiln-effects has resulted in the scientific perfecting of Asahi's beauty.

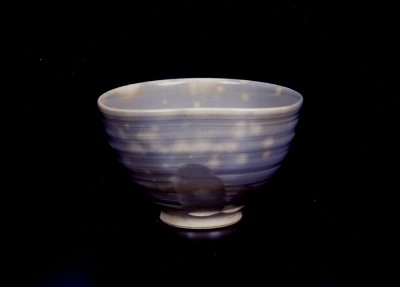

Kase Chawan by Hosai XV

Asahi is known for a subtle yet elegant aesthetic. Formed exclusively out of clay from the Uji region of Kyoto, an area of rolling hills and pristine rivers, it is this clay that gives Asahi's characteristic warm pastels and refined clay flavor -- kiln effects such as spotted Kase, like the spots on a fawn's baby back, and Hanshi, soft colors like the winter morning's rising sun. The Uji clay's unique iron and mineral content combine, through the oxidation and reduction of flame within the Asahi Genyo kiln, to produce trademark Asahi gentleness.

The passing of tradition, however, is not science. "In our family, grandchildren often play at the potter's wheel with their grandfather. My father (Yukoan) played with his grandfather at the wheel, while his grandfather did the same. I suppose one could call it training, but for my children, I think they just like to play with grandpa," says Hosai. A grandfather playing at the wheel with his grandchildren is a heartwarming scene in itself. Yet, this scene is more than mere game, for it, albeit unintentionally, is essential to teaching the children of the Matsubayashi family the basic techniques to making pots. How to spin the wheel, how to form clay in one's hands, how to use simple tools for carving and shaping clay- these traditional techniques are carried from an older generation and passed to a younger generation, thereby preserving the intangible cultural heritage of Asahi.

Kase Chawan by Hosai XV

"Traditional technique? Such is not as important as passing on the spirit of pottery." Hosai's voice gains strength as he speaks of the potter's mental state. "In a family such as mine, the weight of culture is different from a man who's starting out on his own. I have pride in the fact that we have continued pottery for so long, and with this tradition in mind, what we made and will continue to make must always stand the test of time. Not once did I feel pressured into continuing the family tradition of pottery. Rather, I feel it is important for me to make something that none other but my family can make. This is what fans of Asahi expect. This is not pressure. It is a privilege that I embrace."

It is this "Spirit of Asahi" which Hosai has learnt from father Yukoan, as Hosai's grandfather passed away before Hosai was old enough to be taught the tricks to his trade. Hosai's children, however, learn from Yukoan; and importantly, they learn through silent observation, not mechanical instruction. "Through these playful 'lessons,' pottery seeps into their bodies, and unconsciously, they learn how to spin in the correct fashion without 'killing' the wheel."

Traditions live on not only in the daily lives of the Matsubayashi family, but in the land around them. Clay dug and dried by 9th generation Chobei (taken from a nearby hill) is still used by Yukoan and Hosai. Although most tools are newly made for maintenance purposes, Hosai continues to use a piece of deerskin to smooth some of his pieces, a tool once used by Hosai's grandfather. Does such encapsulate a lineal tradition? "It is not the clay nor the tools that capture the Asahi tradition. The tradition is in the hands of my father, my children and myself. It is how these hands interact with the Uji clay which leads to the persevering of tradition." Traditions live on not only in the daily lives of the Matsubayashi family, but in the land around them. Clay dug and dried by 9th generation Chobei (taken from a nearby hill) is still used by Yukoan and Hosai. Although most tools are newly made for maintenance purposes, Hosai continues to use a piece of deerskin to smooth some of his pieces, a tool once used by Hosai's grandfather. Does such encapsulate a lineal tradition? "It is not the clay nor the tools that capture the Asahi tradition. The tradition is in the hands of my father, my children and myself. It is how these hands interact with the Uji clay which leads to the persevering of tradition."

In 1995, Hosai XIV passed the title "'Hosai" to son Yoshikane. Yoshikane became Hosai XV, while Hosai XIV took the name Yukoan. This conferral of title is oft seen in Japanese lineal traditions. Bestowing a name means passing the family throne to the next generation. And likewise, Hosai XV will one day pass his title to his children. And so, the lineal tradition continues.

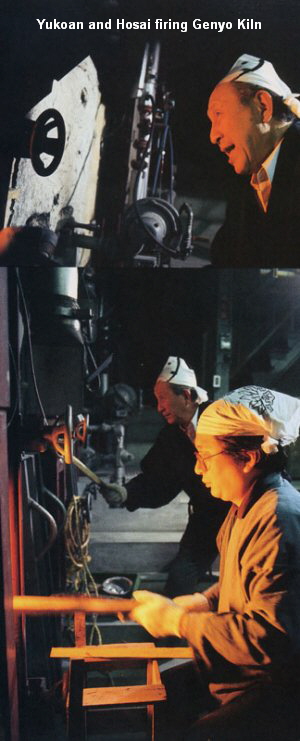

Yukoan (left) and Hosai (right)

This story first appeared in:

The Studio Potter, June 2004, Volume 32, Number 2

Story by Aoyama Wahei

(C) All Rights Reserved

Aoyama Wahei is a graduate of NYU and Oxford University.

He is currently the Ceramic Art Editor for Robert Yellin's

www.e-yakimono.net (this site) and www.japanesepottery.com

For more stories by Aoyama Wahei, please click here

Photos on this page are courtesy of

the Matsubayashi family and the book

"The Asahi Pottery in Uji" by Korinsha.

|