|

Clay forms waiting to be unearthed

By ROBERT YELLIN

for The Japan Times, March 20, 2002

A lump of clay; what forms sleep undiscovered within? There are many ways potters can shape the "earth" they see, the most common is to throw it on a wheel or rokuro. Other ways include tebineri (hand-pinching), himo-zukuri (coil-building), tatara-zukuri (slab-building) or wari-gata (piece-molding).

|

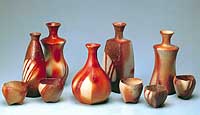

Hidasuki red-streaked ware

|

|

|

Chinese-inspired

3-legged pouring vessels

|

|

|

Seki no Utsuwa

Stone Vessels, whose

removable portions were fired

separately from the body

PHOTOS COURTESY

GALLERY MIDORI-EN

|

|

|

One technique that fascinates me is called kuri nuki, or "carving out." The potter will take some type of tool and slowly whittle into the clay to search for a form. There's no throwing, pinching or coiling; just discovery by digging. The form is born from the clay more than created by the potter. It is a process that requires intuition and trust -- and the results can be quite striking.

Bizen potter Hiroyuki Wakimoto's kuri nuki creations are just that. These primitive clay monoliths are powerful statements, even though most are less than 25 cm tall. His work goes on display today, until March 24, at Gallery Midori-en in Okayama City, (086) 233-2227.

Inspiration flows from many directions into Wakimoto's work. His seki no utsuwa (stone vessels) recall visionary artist Isamu Noguchi, particularly Noguchi's 1968 model for "Octetra," part of a playground installation in Sapporo, or his works based on ancient Haniwa forms. Yet Wakimoto has given his works a harder, sculpted edge, not only resulting from their Bizen brown colors, but also because they are inspired by natural rock forms -- as well as as heavy.

All the seki no utsuwa have removable portions with tones that differ from the main body. Wakimoto fired the parts separately from the body in his four-chambered climbing kiln (noborigama) to achieve this tonal variety. In a Bizen kiln -- or most woodburning kilns, for that matter -- the position in which a work is loaded into the kiln will dictate how the flames and ash dance over it and, thus, produce unique colorations.

The last room of Wakimoto's kiln is where he gets the delightful red fire streaks, known as hidasuki, that mark some of his works. These pieces were wrapped in salt-water-soaked rice straw; this burns off during firing, leaving the scarlet stripes. The technique was originally used to prevent works from fusing together in the o-gama kilns of the Muromachi Period. The 16th-century tea masters took a fancy to the ruby results, and potters have been wrapping their pieces ever since.

Wakimoto is unique these days in that he doesn't, as most Bizen potters do, fire his hidasuki in saggars (saya), thin, protective boxes of fire clay in which fine or delicate ceramics can be safely baked. Without the boxes, speckled-brown ash deposits known as goma (sesame seed) fuse on the bodies, creating a pleasing contrast. In this exhibition, the results are most clearly seen on his sake vessels -- all of which were made by wari-gata, I might add.

Tebineri is another forming technique used by the versatile Wakimoto to create his rather proud and striking three-legged pouring vessels. The prototypes for these date back to China's Neolithic Age and the Dawenkou Culture in forms known as gui (toki in Japanese). Wakimoto's gui, with their peglike feet, protruding bellies and skyward-pointing beaks, look like penguins involved in some ritualistic dance. "Jolly good, right foot forward -- here we go!" the one on the left seems to say. These are playful works indeed.

Other works sure to spark one's imagination are Wakimoto's akari lights. Vertical, often curved slabs, these enclose small hidden "caves" from which an eerie orange glow emanates. The luminosity is almost spiritual and creates a meditative frame of mind. In Junichiro Tanizaki's aesthetic masterpiece "In Praise of Shadows," he bemoans our "senseless and extravagant" reliance on electric lighting that reveals all and leaves no room for mystery. I personally despise fluorescent lightning -- and all the neon ads that confuse the mind into thinking that life is about mass consumption. To have one of Wakimoto's akari in a room sets the mood for light and shadows to dance over the imagination, thus allowing us to connect with our deeper selves and a universal presence.

And in a way, that's what the art of clay is all about: the art of being here, now, fully awake to the ever-flowing present that is continually connected to the past and future. Just the way Wakimoto has done with his clay discoveries.

The Japan Times: March 20, 2002

(C) All rights reserved

|