|

Redeemers with Feet of Clay

By ROBERT YELLIN

for The Japan Times, Jan. 8, 2003

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ido Chawan

by Tsujimura Shiro

|

|

|

|

|

Foot of Ido Chawan

ABOVE PHOTOS

COURTESY OF

NIHONBASHI MITSUKOSHI

|

|

|

Of the 14 ceramic objects designated as national treasures in Japan, the fact that eight are chawan (tea bowls) is a clear sign of their importance in the culture.

Of these eight, five are actually Chinese tenmoku brought here in the Kamakura (1185-1333) and Muromachi (1333-1568) periods; another is a Korean Ido ware from the Choson Period (1392-1910); one is Japanese Shino ware from the Momoyama Period (1568-1715); and one is Koetsu Honami's (1558-1637) "Fuji" chawan from the Edo Period (1603-1867). For more on tenmoku, ido, shino, and other ceramic styles, please visit our Guidebook.

It has, however, taken me years to even begin to be able to fathom what is going on with chawan in Japan; to understand their "spirit," in which simplicity is depth and intelligence, asymmetry is beauty, and cracks and "flaws" are attractive. When I first came to Japan back in the 1980s, these concepts were as alien to me as having lunch on Mars. Yet all these graceful qualities are found in chawan.

In "Wind in the Pines" (a fine book on the Way of Tea as a spiritual path, compiled and edited by Dennis Hirota), I was struck by a paragraph on tea utensils:

"They are perfect in that, grasped in the light of wisdom-compassion just as they are, they are taken out of time and transcend all the petty judgments and ambitions that fill our lives. They are also imperfect in that they participate in our existence and we in theirs, and therefore, they are subject to all the flaws and infirmities of our lives. By this measure, those objects are most treasured that awaken one to this dual nature of one's existence, that draw one beyond oneself into a world of love that is no-self, and that work, as embodiments and instances of Buddha's compassion, to save one just as one is."

That's a lot to ask for, and find, in a chawan.

Yet, most collectors of chawan -- and I know I'm generalizing here -- have mainly seen tea bowls "that superficially look like chawan [the bowls produced by most contemporary Japanese potters and almost all foreign potters here], yet chawan they are not." These words were spoken to me years ago by the Bizen great, Anjin Abe -- and I've never forgotten them.

What he's saying, in essence, is that there's more to a chawan than merely its shape. According to philosopher Shin'ichi Hisamatsu (1889-1980) writing in "Zen and the Fine Arts:"

"With an ordinary bowl much attention is paid to the shape or silhouette of the body, and little to the foot or lip. With a tea bowl for the Way of Tea, however, importance is attached to the lip, inside surface and foot."

Not a whit less essential to the creation of a true chawan, I may add, is the spirit of the potter. For without an infusion of the craftsman's deep understanding of himself, and of the mysteries of clay and fire, a tea bowl remains an empty shell.

Chawan can be classified into three basic categories, according to country of origin: China, Korea or Japan. The Chinese styles include tenmoku wares and the 22 variations on them -- seiji (celadon), hakuji (white porcelain), sometsuke and shonzui (underglaze cobalt blue), aka-e (overglaze red) and iro-e (overglaze enamel), to name just a few.

From Korea there is inlaid celadon, Mishima ware (also inlaid), kohiki-de (white slip), oido ("large well," bowls with a deep "pool"), hakeme (brushed white slip), kata-de (similar to white porcelain), soba (open-faced, rough bowls, the color of buckwheat), kakinoheta (brownish "persimmon" chawan), irabo (yellowish glaze), goshomaru (the prototype of the more famous Oribe ware) -- and many others! See Glazes and Techniques in our Guidebook for more.

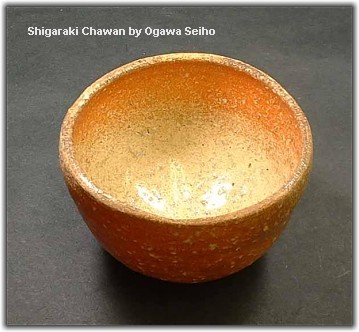

From Japan we find copies of Chinese wares, such as the early Seto wares made during the Kamakura and Muromachi periods; works influenced by Rikyu's wabi-cha tastes, such as Bizen, Shigaraki and Raku; and pottery from Mino Province (part of present-day Gifu Prefecture), including hikidashi-guro, Ki-Seto (Yellow Seto) and Shino ware. See Mino for more.

Furuta Oribe (1544-1615), the warrior and celebrated tea master, favored the two native stonewares of Bizen and Shigaraki, as well as Iga ware and Kyushu wares such as Karatsu and Takatori. He also expanded the Mino world with a Mino-Iga hybrid and his own Oribe ware.

The arbiter of tea tastes in the Edo Period was Kobori Enshu, who nominated the "seven kilns" of Takatori, Agano, Akahada, Kosobe, Zeze, Shidoro and Asahi as producers of fine chawan. The same period also saw the creation of colorful, new Kyoto stonewares, such as Ninsei and Kenzan. More information on these and many other lesser-known Japanese styles can be found in "Chawan Kamabetsu Meikan" by Kuroda Kazuya.

The above is all academic information. It enables us to classify and understand the origins of different chawan styles. Yet how does it help us to truly "see" a chawan? What else can we do to really "get" what chawan are all about?

What it all boils down to is very simple and very Zen -- unless you are the sort of person who, when you stand under the wide sky, whatever the weather, is simply not amazed, for there is no difference between that experience and holding a profound chawan. The soul of a chawan will evade such people as thoroughly as if they tried to grasp some mountain mist.

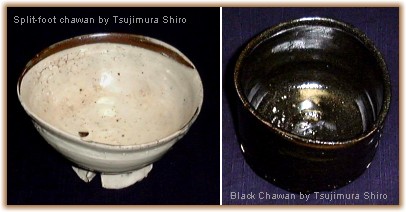

Ultimately, when you pick up a true chawan, you're also grasping a potter's soul, since it takes much more than mere technique to create such a bowl. I would say that in the contemporary Japanese ceramic scene, only a handful out of thousands of potters are making chawan that will stand the test of time. One of them is Tsujimura Shiro.

In his latest exhibition -- at Nihonbashi Mitsukoshi's sixth-floor gallery from Jan. 14 to 20, 2003 -- Tsujimura is showing mainly one style: simple and deep Ido chawan (see photos at top of page). Of Korean lineage, and dating from the Choson Period, Ido chawan are characterized by a high foot and a wide, flaring body. The color of the glaze is usually a neutral buff tone that perfectly complements the frothy emerald matcha.

Tsujimura has devoted much of his life as a potter to Ido chawan, and a spirituality emanates from these perfectly imperfect chawan. Many of the bowls already have an ancient feel; some are large enough for one's whole face to disappear inside; while others, known as tabi-jawan (traveler's chawan), are only slightly larger than a sake cup. The all-important kodai (foot) is strong on Tsujimura's Ido chawan; while on many there is a delightful crawling quality to the icing-like glaze, known as kairagi.

Amid our daily bustle, a chawan offers a hand-held sanctuary for deep pondering to refresh the spirit and reunite it again with nature. And right now, indeed, we need such refuge and reflection.

The Japan Times: Jan. 8, 2003

(C) All rights reserved

LEARN MORE ABOUT TSUJIMURA SHIRO

Exhibit Review and Photo Tour, 2001

Another JT Story about Tsujimura, 2001

FOR OTHER CHAWAN-RELATED STORIES

Ajiki Hiro (Chawan Exhibit)

Atsuo Akai (Chawan Collector)

Kato Yasukage (Chawan, Gifu)

.

|