|

Click here for

index to all

Yellin stories for

The Japan Times

What is Mino?

Shino, Seto,

Ki-Seto, Oribe

Yellin's gallery

sells pieces from

the kilns of Japan's

finest potters |

|

|

Japan's Tea Pots

Made by an American Potter

By ROBERT YELLIN

for the Japan Times, Sept. 9, 2004

ALSO SEE: Richard Milgrim's Web Site

|

|

Richard Milgrim Exhibition

From Sept. 14 to 20 (2004) in the sixth floor gallery at the Mitsukoshi department store in Nihombashi, Tokyo. Milgrim-san will be in the gallery each day of the exhibit, and tea will be served daily from 11 am to 4 pm in the gallery.

Concord Kiln Chawan

Painted Shino Water Container

and Tea Caddy

Richard Milgrim

Black and White Glaze

Tea Caddy and Silk Pouch

PHOTOS COURTESY MITSUKOSHI

Richard Milgrim's

Web Site:

www.teaceramics.com

|

|

|

|

|

The stereotypical image of a chadogu (Way of Tea) potter is of an elderly gentleman with a wispy beard and sharp piercing eyes, clad in a samue (artist's working clothes). You would assume he had come from a family dating back generations and that his lineage was of supreme pride and importance in Japan's tea world. Owning one of his works would be a sign of taste and status in this country's brand-conscious society.

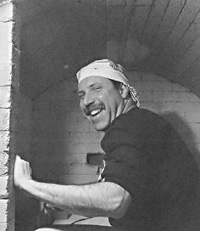

Now let's throw all those images out through the shoji door and imagine this: A strapping chadogu potter who hails from White Plains, New York; he is steeped in chadogu traditions, has a kiln in the hills outside Kyoto and in Concord, Mass., and creates chadogu based on age-old formulas with an added something that gives birth to works of distinction.

Sound far-fetched? Well, there is such a potter and his name is Richard Milgrim. He'll be exhibiting some 70 of his chadogu works in Tokyo from Sept. 14 to 20 (2004) in the sixth floor gallery at the Mitsukoshi store in Nihombashi (Tokyo). Milgrim is one of a select number of western potters working in Japan. He began studying here 25 years ago and worked as an apprentice with master potters in Kyoto, Hagi, Bizen and Mino before establishing his own studio in 1984.

"I have dedicated the past twenty-four years working to contribute to the field of chadogu in Japan and throughout the world," Milgrim wrote for an exhibition in San Francisco last year. He continued, "Using traditional materials and techniques, with one eye on the past and the other looking towards the future, my goal is to create works of art with a timeless quality. Works that simultaneously maintain their inherent function as chadogu, yet also capture a beauty that can transcend geographical and cultural boundaries and be appreciated by the uninitiated as well as the tea practitioner."

Milgrim has succeeded in his goal, by producing graceful chadogu. Using a virtual what's what of Japanese chadogu ceramic styles -- these include Shino, Seto, Ki-Seto, Oribe (all Mino styles), Karatsu and Yakishime (a high-fired unglazed style) -- along with his work fired in Concord; he has brilliantly incorporated these styles into his pieces, all on his own terms. Most of Milgrim's output revolves around the all-important chawan (tea bowl). So many artistic and technical aspects go into the making and firing of a chawan, but only a handful of non-Japanese artists have ever attempted to make one, let alone create a worthy one. His chawan awaken in the user a bond of humanity. Their beauty speaks to the heart, leaving out the fenced-in mundanities of the mind.

They also serve their main function, which is to set off the frothy emerald-green matcha (type of Japanese green tea) and bring a simple, deep pleasure to the partaking of it. His Shino chawan, in particular, stand out -- with their dynamic underglaze iron brushwork depicting reeds, mountains, spirals and geometric patterns. Works fired in his Concord kiln have a kinship with his Japan-fired works, yet display a totally fresh approach to mixes of glaze and color combinations.

Milgrim finds a good chawan should have "strength, freshness, spontaneity, balance, style and interesting form when viewed from all angles. It should be easy to use, and have movement, not all necessarily in that order."

While making chawan the potter says he experiences many varied thoughts, feelings and moods. Those emotions come out very clearly in his chawan; there's joy, moodiness and humor as well as a certain austerity here. Almost all his chawan draw on classical examples of the Momoyama period (1568-1615), yet there is certainly that "something" about them that is all-Milgrim, especially in the imaginative use of design on his Shino chawan and the way he overlaps glazes on others.

The kodai (footring) is a key part of a chawan, even though it is hidden from view until the tea has been drunk. Then, without fail, a tea votary will turn over the chawan, being careful to lift the kodai but a few centimeters off the tatami, to examine it. Why? Well, a few reasons, the main one being that the skill and mind-set of the maker are most clearly seen in the kodai. Other reasons include viewing the tsuchi-aji (clay flavor), which is often glazed over and therefore seen only on the kodai; the Japanese dig good tsuchi-aji.

Be sure to notice this aspect of Milgrim's chawan, because he communicates with his clay and allows it to have a say in how it wants to be formed. Sometimes he'll hear it say, "Do it this way and take a little weight off here," or "That kodai doesn't suit me," or "I don't want to be round!" It only takes a few minutes at most to throw a chawan, yet after that comes the carving of the body, which takes Milgrim approximately 30-40 minutes per piece.

That is but a blink in time, especially ceramic time, where the clay is as old as the earth and the spirit of the maker is immeasurable. Milgrim's ceramic art holds a special place in the Japanese ceramic scene and will surely melt into the tea psyche of any who stand before, and hopefully use, his chadogu. Chadogu that would make any great tea masters of ages past bow in silent appreciation.

Richard Milgrim will be in the gallery each day of the exhibition. Tea will be served from 11 a.m. to 4 p.m in the gallery and be sure to ask him about the special honor he just received for his Concord kiln.

Autumn heralds the start of bunka no kisetsu (culture season) and there are many exhibitions to visit. Ones I would recommend include Mino master Hori Ichiro's showing at Nihombashi Takashimaya's sixth floor gallery from Sept. 15-21, 2004. Hori is one of only a handful of traditional Mino artists who fire the old-fashioned way in a wood-burning kiln. He creates Shino of the highest order. His Black Seto and Ki-Seto are also magnificent.

Just back from a year studying in Scotland is Kyoto porcelain specialist Kondo Takahiro. He'll be showing his porcelain and glassworks at Yufuku Gallery (opens new browser window), Minami-Aoyama 2-6-12, tel: (03) 5411-2900 until Sept. 18, 2004. This is Kondo's first Tokyo exhibition since his return. For more on Kondo-san from EY-NET, click here.

Three rising stars of the Mino world are holding joint exhibitions in Tokyo and Shizuoka; they are Kato Yasukage, Tsukamoto Haruhiko and Kato Toyohisa. All have a unique sculptural quality to their work that departs from classical forms -- very much Mino for the 21st century. They are in Tokyo at Ginza Matsuzakaya 6-10-1, tel: (03) 3572-1111 from Sept. 22-28 and in Shizuoka at Matsuzakaya, just opposite the station, tel: (05) 4254-1111, Oct. 20-26.

The Japan Times: Sept. 9, 2004

(C) All rights reserved

LEARN MORE

|

|

|