|

Reprinted with permission from The Kyoto Diary, Volume 7, Number 2 (Quarterly Magazine; this story first appeared in its Oct/Nov/Dec 2002 edition). Please note that the photos in this article are from e-yakimono.net and not the photos that appeared in the magazine.

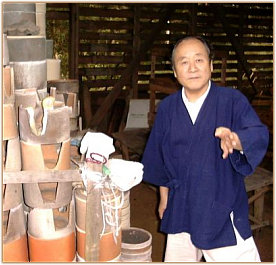

Kato Kozo

21st Century Potter Resurrects 16th Century Techniques

by Steve Beimel

Kato Kozo approaches slowly, solemnly, as if every movement matters. He opens the gate, greets me, and leads me onto the wooded rural property that he calls home in his native town of Tajimi, a major ceramics center, outside Nagoya.

A number of years ago, this celebrated Shino-ware potter, now 66, brought a 250-year-old farmhouse here and had it reassembled, piece by painstaking piece. In this simple yet timelessly elegant home, with its brown wooden beams, golden tatami mats and sesame colored walls, we sit and talk of his long career as an artist and his efforts to revive the ancient techniques of his craft.

Today, Kato-san is one of Japan's leading potters, but he began as a painter. In 1962, at age 25, he won the prestigious Young Artists Award in the national Japan Art Exhibition. "As a result," he says, "I was seriously considering leaving Tajimi and my job at the local government ceramics research institute, and going to Tokyo to work and study painting."

|

|

SIDEBAR. Just as he rebuilt and restored his ancient farmhouse precisely to its original form, he wants to leave the legacy of the Momoyama potters of this Mino district to the next generation. That's why he uses the Momoyama anagama, and that's why he hosts a monthly meeting at his home for local potters to share, study and ruminate on ancient traditions.

Ki-Seto Tsubo (jar) with rich

amber tones mixed in with a

dark yellow "feathery" glaze.

That's also why he uses a rare hand-push wheel, which he can rotate with the tip of one finger, instead of the electric or kick wheels favored by modern potters. It allows him, he says, "to experience very subtle changes in the clay. I can feel where my fingers were on the previous revolution."

Perhaps the reason Kato-san chooses the slowest, least productive methods is that he calls the work of an artist learning through pain. "The process requires heavy use of the physical body," he says. "Split the firewood, prepare the soil, make a shape, place it in the kiln. I ride the rhythm of this chain of steps in the act of producing a stoneware pot. It can't be learned by short cuts and easy ways. You can shorten the time, but if you pay too much attention to technical methods, you get farther away from the creative spirit of the artist."

"I recently found a broken shard from the Momoyama period," Kato-san says. "You could see one of the potter's fingerprints on it, and I matched my own fingerprint to it. It was an experience beyond words, beyond figures and facts."

|

|

|

|

|

Fortunately for the world of pottery, a teacher encouraged him to stay on. "He said that if I was looking to create beauty, there was an inexhaustible supply of clay right here for my use," Kato-san remembers. (see sidebar)

Kato-san worked and studied at the ceramics institute until 1970, so he knew the most cutting-edge ceramics technology of the time. "But the more I investigated scientific techniques," he says, "the more I wanted to think more simply. Finally, I grasped the profound simplicity of this work: creating ceramics is a matter of preparing the clay, making a shape and firing it."

Kato-san returned to the ways of the ancients, forgoing modern gas and electric kilns in favor of a simple wood-fired anagama kiln replicated from those of the Momoyama Era (late 1500s), based on extensive research. Called a Mino Large Kiln and measuring six feet wide by six feet deep, it was only used for about 40 years by potters of this Shino region. Toyotomi Hideyoshi, the national leader, invaded Korea, and the Korean potters he brought back introduced the climbing step kiln that became the standard. "Though the anagama is an extremely inefficient kiln," Kato-san says, "I hoped that it would allow me to recapture the essence of legendary Momoyama-Era Shino pottery."

More efficient, modern kilns maintain a steady heat, but the anagama uses wood, with its many elements, impurities and uncertainties. At first the flame practically roars. "The burning wood breathes," Kato-san says, "and when it comes face-to-face with the big roaring fire, we experience an uplifting, an exaltation, a heightened sense of excitement." Then it seems to quiet down but continues to breathe for up to several days. Ash forms and flies around inside the kiln in unpredictable patterns.

It all helps to create Shino ware's distinctive whitish glaze (ash/feldspar), and equally distinctive pinhole texture, referred to as "citron skin" by tea masters.

"It is not I who creates the results," Kato-san insists. "Once I put the pot in the kiln, I give it all up to the fire. My ego has been tossed away."

With any kiln, there is a magical moment when the potter peeks inside after a firing. With Kato-san's idiosyncratic anagama, it's even more so. "It is a complete surprise when I open the door," he says. "The heightened sense of expectation and surprise continues until I remove the very last piece."

Kato-san might fire as many as 220 tea bowls at one time, but he might keep only eight pieces from each firing - his internal artistic standards are that high. "To people accustomed to working rationally and efficiently, this approach probably seems unbelievable," he laughs. "Usually a potter expects to discard eight pieces and keep 212! Since I throw so many pieces away, some people might think that my skills are lacking."

Not really: recently I was here with a group during a kiln opening. As Kato-san selected his few choice pieces and rejected the rest, several people asked where he kept his pile of rejects.

If they knew what really happens to them, they might be horrified. "Some days after making my initial selection from the newly opened kiln, I may choose a few more pieces," Kato-san says. The rest, he breaks.

|

|

SELECTED QUOTES

Shino tsubo with rich crackled

glaze with finger wipes and

lively hi-iro fire colors

"The more I investigated scientific techniques, the more I wanted to think more simply. Finally, I grasped the profound simplicity of this work: creating ceramics is a matter of preparing the clay, making a shape and firing it."

"Once I put the pot in the kiln, I give it all up to the fire. My ego has been tossed away."

"Gas and electric kilns of today are so efficient and scientific. Potters have a great deal of control over the process and are thus able to produce a very high percentage of quality pieces. They have mastered fire. However, for me, the idea of controlling fire is a strange concept. By surrendering to the power of the flame, I experience a kind of inner calm. You could call it an Asian or Buddhist way of thinking. It is like a prayer of surrender, to be a part of a wonderful process, but not in control of it."

"I think that all Japanese potters who use highly efficient, controllable kilns would enjoy trying this kind of kiln, to load it up with firewood, to fire their pots on a big flame, that they have this kind of yearning. Any potter I ask always says so. Just one time, to fire up this kind of kiln."

"The burning wood breathes, and when it comes face-to-face with the big roaring fire, we experience an uplifting, an exaltation, a heightened sense of excitement. At that moment, I intensely feel myself firing these works from the earth itself. It is a full and intense awareness of all that exists in present moment. The bewitchment, the fascination of that moment is completely irresistible for me. The process here is so much more important than the result. Split the firewood, prepare the soil, make a shape, place it in the kiln. I ride the rhythm of this chain of steps in the act of producing a stoneware pot. I am totally captivated by the process."

"Though there is an economic pressure for me to keep more pieces, I can only select pieces that I am sure are really right. Otherwise, there is a danger that my standard of beauty will fall."

|

|

|

|

|

Becoming an Artist in Hard Times

Unlike many traditional Japanese craftsmen, Kato-san did not come from a line of potters. His father was in the raw-silk thread business, and the family's small factory was confiscated during the war. During the post-war years, Kato-san went into the arts solely on his own, with no outside support.

"I don't know if young people today can grasp this," he says, "but that was a time when people were hungry, both physically and spiritually." Although he started as a painter, "in those days, a person could not earn a living by painting. Looking at the other painters I knew, no matter how many paintings they sold, they could not make ends meet."

"I sold almost nothing either," he says. "Try to imagine the gratitude we felt towards anyone who actually bought our works! It wasn't until about 1960 that things began to really turn around economically here, when our work, the work of craftsmen, began to be recognized. That's why, even today, I have a keen appreciation for having food on the table."

A Special Tour of Japanese Pottery:

esprittravel.com/ja_ceramics.htm

From Nov. 2 to 14

Maximum Participants: 24

Tour Leader: Steve Beimel

Guest Lecturer: Robert Yellin

On this journey we'll discover the beauty of both the incredible ceramics and lush countryside of southern Japan. Joining us as a guest lecturer on this in-depth study tour will be Robert Yellin, one of the foremost experts on Japanese ceramics. Between Robert and the many highly skilled potters we'll meet, expect to return home having received a real education in ceramics, from mingei pottery to high-fired, low-fired, glazed, and ash-glazed stoneware.

We will visit the great pottery centers of Kyoto, Shigaraki, Bizen, Karatsu and Hagi, explore the unique styles of each and learn about both traditional and contemporary ceramics. Throughout the tour we will have many opportunities to be guests in potter's studios, where we will hear about their lives and their art. We will also get to see the work of various other craftsman and to enjoy the mastery of these artists.

We'll travel Japan's rugged hills and lush valleys, which are studded with thousands of puffing, glowing kilns, producing the beautiful ceramics for which the region is well-known. We'll visit small towns full of artisans still working with traditional materials in both ancient and innovative ways. And all along the way, we1ll immerse ourselves in the sights, sounds, flavors and feel of Japan, meeting artists, craftspeople and storytellers, traveling as the Japanese do and staying at outstanding inns.

Please visit http://esprittravel.com/ to learn more about The Kyoto Diary, the upcoming Nov. 2003 tour, and other activities of this organization.

Kato fires in a traditional half underground anagama.

The inside of the kiln is pictured above.

For more on artist Kato Kozo:

|