|

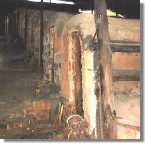

Kilns come in many varieties, from wood-burning to electric, fuel oil, natural gas, coal, or propane. The heating method greatly influences the pottery -- e.g., for natural ash glazes, potters prefer the wood-burning anagama (see adjacent photo), for it produces fly ash, which settles on the pieces, melts, and creates a natural ash glaze that cannot be achieved with any other type of firing.

Learning all there is to know about kiln firing is a daunting task, for no two firings are ever exactly the same. Even the great masters cannot control the kiln to perfection -- there are just too many variables -- how much air, how much wood, what fuels to use, when to use them, how to control temperatures, how much stoking, how to stack the pieces, where to place the pieces. The potter controls about 85% of the process but other factors are beyond control, like weather, wood-condition, and kiln atmosphere, which are left to the kama no kami or kiln god.

The traditional kiln types of Japan are explained below, followed by a short history of the kiln in Japan.

Anagama. Single-chamber kiln, or tunnel kiln, introduced to Japan from Korea in the fifth century; wood firing; favored by potters who prefer natural ash glazes Anagama. Single-chamber kiln, or tunnel kiln, introduced to Japan from Korea in the fifth century; wood firing; favored by potters who prefer natural ash glazes - Noborigama. Climbing kiln; wood-burning; main type of kiln used in Japan since the 17th century; largely preferred for glazed ware as it gives consistency and predictability to kiln output

- Renboshiki noborigama. Multi-chambered climbing kiln

- Makigama. Wood-fired kiln

A SHORT HISTORY OF THE KILN IN JAPAN

Ancient Japan

The anagama (single-chamber kiln, wood-fired) was first introduced to Japan from Korea in the fifth century. Prior to that, firing in Japan took place in outdoor bonfires, open pits, or ditches. Since the temperature was unlikely to exceed 700 degrees, Japan's ancient wares are typically referred to as low-fired earthenware -- ware that is largely water-soluble. The two styles associated with ancient Japanese pottery are Jomon and Yayoi (see Timeline for more). During those ancient times, the potter's wheel and the kiln were not yet used.

Fifth Century - Introduction of Anagama and Potter's Wheel

The introduction of Sueki (Sue) ware to Japan from Korea in the middle of the fifth century marks a major turning point in Japanese ceramics, as both the anagama (single-chamber kiln) and the potter's wheel enter the Japanese scene. Sueki was fired to yellow heat, between 1100 - 1200 degrees centigrade, in a reduction atmosphere, and generally made on the wheel. The Bizen, Shigaraki, and Tamba styles stem from the Sueki Tradition. Sueki ware is typically gray, as a common firing technique at the time was to introduce excess fuel at the very end of firing, turning the surface of the pots to charred gray. This technique is called Kaito in Chinese.

17th Century - Introduction of Noborigama

For many centuries the anagama continues to fire a wonderful creativity in Japanese aethestics and ceramics. But in the early 17th century, the anagama loses its importance and is replaced by the noborigama (multi-chamber climbing kilns).

There are a number of reasons for this change. First, the multi-chambered noborigama greatly improved productivity -- ten to twenty times more pots could be created in one firing compared to the volume of the average anagama. Second, for glazed ware, the noborigama brought a greater level of consistency and predictability to output, as well as economies of scale. As we move closer to the modern era, mass production comes into favor, and the anagama is more or less abondoned.

Current Kiln Scene

The anagama has enjoyed a revival in the last few decades thanks in part to the work and efforts of Furutani Michio (1946-2000) and Yasuhisa Kouyama. Furutani (deceased) is considered by many to be the King of Anagama in modern Japan. Today there are hundreds, possibly thousands, of potters using an anagama in Japan. In the West, moreover, the anagama is making strong headway (it has only been in the West for the past 20 or 30 years), so much so that it has become part of the jargon of Western potters.

FIRING TECHNIQUES

Click here to learn about Matsuzaki Ken's unique firing technique for Shino ware in a specially constructed wood-burning noborigama. Click here to learn about Matsuzaki Ken's unique firing technique for Shino ware in a specially constructed wood-burning noborigama. - Click here to learn about the "bottoms-up" firing technique of Bizen artist Abe Anjin.

- Firing Yakishime. Basically uses either anagama or noborigama kiln. Temperatures can reach 1350 celsius (some push it up to 1500 degrees) and a kiln can be fired for up to sixty days.

- Click here for a brief photo essay on potter Mitsuru Isezaki, who allows great build-ups of ash on his kiln floor to create some stunning yohen pots. Yohen literally means "changed by the fire/flame."

- Click here to learn about the activities of Mori Togaku, one of Japan's most respected Bizen potters, and an extraordinary artist who is building giant kilns in the same style used centuries ago.

|